Introduction

After World War II, nations around the globe joined in Geneva, Switzerland to sign treaties and agreements on how to treat people at times of war. These agreements and standards became known as the Geneva Conventions. Article 13 of the 1949 agreements stated that “Civilians are to be protected from murder, torture or brutality, and from discrimination on the basis of race, nationality, religion or political opinion.” Despite the international agreements, countries around the world continued to violate agreed-upon human rights. One such violation was the March 16, 1968, My Lai Massacre during the Vietnam War.

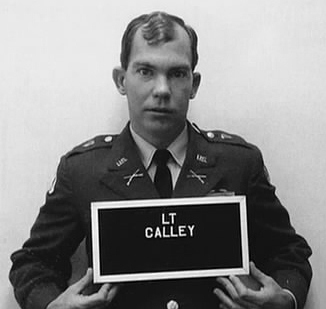

There were many events that led up to the My Lai Massacre. American soldiers occupying Vietnam were constantly attacked by the Vietcong, the army of Vietnamese Communists. The Vietcong were guerillas , meaning that they fought quickly and quietly. U.S. soldiers saw their friends killed and injured from unknown sources. This traumatized, frustrated and angered them. Captain Ernest Medina instructed the Charlie Company of American soldiers of an upcoming mission to the Sơn Mỹ village. The village was located in the Northern part of South Vietnam province of Quang Ngai. The mission’s purpose was to search for Vietcong guerillas and, according to later court testimony, take revenge upon their enemy. On March 16, 1968, U.S. troops led by Lieutenant William Calley attacked a part of Sơn Mỹ called My Lai. In the span of a few hours, U.S. troops killed hundreds of Vietnamese civilians including women, children and seniors. Approximately 500 Vietnamese people were killed, with few survivors. In addition to killing the villagers, U.S. soldiers committed other war crimes. They burned homes, killed livestock, and poisoned the water supply.

The events of the My Lai Massacre were concealed at first. An investigation into the massacre by Major Colin Powell found “isolated cases of mistreatment of civilians and POWs…relations between soldiers and Vietnamese people are excellent.” The U.S. government hid facts of the incident for more than a year. The hidden file was known as the “Pinkville Incident.” Army officials reported My Lai as a victory. They celebrated one hundred twenty eight Vietcong killed with three weapons captured. This was the official story until late 1969.

Seymour Hersh was the first to share the true story of the My Lai Massacre to the U.S. public. Ronald Ridenhour's detailed account of the mission helped Hersh share the story in November 1969. The news of My Lai further increased anti-war sentiments about the Vietnam War. The Department of Defense also launched a full-scale investigation into the event. In addition, William Calley was court-martialed, or tried in a military court. The court martial of Lt. William Calley began on November 17, 1970 and ended with his conviction on March 29, 1971. Lt. Calley was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison. Captain Medina was charged with murder but acquitted, or found not guilty in the court. Twenty-five other soldiers were tried but were also acquitted. Calley’s sentence was contested in different courts. President Nixon even worked to reduce his sentence. Calley's sentence was reduced multiple times as well. It was reduced from 20 years to 10 years. He ultimately served only three years on house arrest. Calley was then freed by 1974.

What was the impact of My Lai?

News of My Lai lowered soldier morale and increased anti-war feelings. Over the next few years, Nixon began to pull troops from Vietnam. Soldiers would also implement fragging. According to History.com, “fragging was used to describe U.S. military personnel tossing of fragmentation hand grenades…usually into sleeping areas to murder fellow soldiers.” Soldiers used it to disobey and express anger towards superior officers. Protesters across the U.S. demonstrated in schools, universities and the capital. Opinions of the war were divided due to the massacre, Calley’s conviction, and the war.

Newspapers in North Carolina began reporting the story of My Lai or “Pinkville” around November 1969. Opinions, like those in the larger United States, were mixed and divided. Some were critical of the culture and events surrounding the massacre. Others discussed how the event was “not typical.” They said that the “prestige of the United States around the world” was the “greatest victim of the ‘Pinkville’ incident.” Public opinion in North Carolina reflected these divided opinions. Students across college campuses in North Carolina were very opposed to the massacre. For example, students at East Carolina University quickly organized to protest the war after news of the massacre became public.

The My Lai Massacre further increased anti-war feelings surrounding the Vietnam War. It also violated the 1949 Geneva Conventions. It is still regarded today as a significant war crime in world history.

Glossary:

- Viet Cong: Northern Vietnamese Army (NVA); the Communist guerilla movement also called the National Liberation Front

- Vietnam War: A conflict in Vietnam that lasted 20 years (1955-1975). Significant U.S. involvement began in the 1960s.

- Charlie Company: America Division’s 11th Infantry Brigade

- POW - Prisoner of War

- Court-martial: A formal legal process carried out by the U.S. Military to try servicemembers who violate military laws

- Geneva Conventions of 1949: Formal, international agreements on the treatment of non-combatants or civilians; it was signed by over 100 countries including the U.S.

- Massacre: an event in which many people are killed

Guided Reading Questions:

- What is the name of the international convention(s) that the My Lai Massacre violated?

- Who was the leader of the American soldiers during the My Lai Massacre?

- What was the secret code name of the massacre before it became known to the public?

- Name one college campus where students protested the Vietnam War and the massacre.

Critical Thinking Questions:

- Should a government disclose incidents like My Lai to its people?

- Were the court sentences issued in response to the massacre appropriate?

- Was "fragging" justified?

- Can you think of current world events that might violate the Geneva Conventions today?

References:

“A Journalist Reports Fragging of US Officers.” Alpha History. 1972. https://alphahistory.com/vietnamwar/journalist-fragging-us-officers-1972/ (accessed on September 20, 2023).

“BACKLASH OVER PINKVILLE.” The Kings Mountain Herald, December 18, 1969. https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn98058845/1969-12-18/ed-1/seq-2/#... (accessed on October 15, 2023).

Bond, James E. “Protection of Non-combatants in Guerrilla Wars,” in William & Mary Law Review 787. Seattle: Seattle University Law School, 1971. https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1705... (accessed on September 15, 2023).

“Despite Witness Reports, Rivers Says No Massacre.” The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, N.C.), December 11, 1969. https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92073228/1969-12-11/ed-1/seq-6/#... (accessed on October 15, 2023).

“‘Fragging’ on the rise among U.S. military units.” History.com. 1971. https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/fragging-on-the-rise-in-u-s-... (accessed on September 20, 2023).

Hersh, Seymour. “The My Lai Massacre.” The New Yorker. January 14, 1972. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1972/01/22/coverup (accessed on September 15, 2023).

"How the Army’s Cover-Up Made the My Lai Massacre Even Worse.” History.com. August 30, 2018. https://www.history.com/news/my-lai-massacre-1968-army-cover-up (accessed on September 15, 2023).

Linder, Douglas O. "The My Lai Massacre and Courts-Martial: An Account.” University Of Missouri-Kansas City School of Law. https://famous-trials.com/mylaicourts/1656-myl-intro (accessed on September 15, 2023).

“My Lai Massacre: Vietnam.” History.com. March 30, 2023. https://www.history.com/topics/vietnam-war/my-lai-massacre-1#charlie-com... (accessed on September 15, 2023).

“Three criteria for evaluating the ‘Pinkville’ incident.” Smoke Signals (Murfreesboro, N.C.), January 30, 1970. https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/2015236578/1970-01-30/ed-1/seq-7/#... (accessed on October 15, 2023).

Tucker, John A., PhD. “ANTI-WAR PROTESTS, 1969.” Chronicles Our History, East Carolina University. October 14, 2020. https://collectio.ecu.edu/chronicles/About/Anti-War-Protests (accessed on October 15, 2023).

“Primary Sources: Vietnam War.” Florida Atlantic University Libraries. https://libguides.fau.edu/vietnam-war/us-military-my-lai-massacre (accessed on September 15, 2023).

Raviv, S. “The Ghosts of My Lai.” Smithsonian Magazine. January 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/ghosts-my-lai-180967497/ (accessed on September 15, 2023).

“Women, Children Massacred. The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, N.C.), November 21, 1969. https://newspapers.digitalnc.org/lccn/sn92073228/1969-11-21/ed-1/seq-1/#... (accessed on October 15, 2023).