Lewis Hine, photographer for the National Child Labor Committee, documented child labor across the United States in the first decades of the twentieth century.

“Labor” was not a new concept to children who went to work in the mills. Many spent their earliest years on their family’s farm, helping their parents with chores and working in the fields. Making a living on a family farm was difficult, especially when the family was renting the land from a large landowner. Everyone on the farm worked hard at raising enough crops and livestock to support the family, but farm families rarely made a profit. Some went into deep debt during years with poor crops.

Mill owners looking for employees capitalized on the frustrations of farm families. They sent recruiters to rural and mountain farm areas to hand out pamphlets singing the praises of mill life. For families struggling to grow enough food to feed themselves and make a small profit, the prospect of a regular paycheck was appealing. Ethel Shockley and her husband moved off the farm they were renting in Virginia to work in the cotton mills of Burlington, NC in 1921. They made about 75 cents a day working on the farm and could make 2 dollars a day working in the mills. Like the Shockleys, thousands of farmers across the South made the decision to trade in their self-sufficient farm life for life in the mill village, and they brought their children with them.

During the late 19th and early 20th century, the few laws prohibiting child labor were moderate and rarely enforced. In North Carolina, the age limit was 13 for employment in factories such as mills, and children under 18 were allowed to work up to a shocking 66 hours per week! Mill owners had to “knowingly and willfully” break these laws before they could be convicted. Even more lenient laws were in place in South Carolina, where the age limit for factory workers was 12 years old. However, orphans and children with “dependent” parents (those too sick to work) could work at any age and any amount of hours. These laws were rarely, if ever, enforced. Former child workers remember scrambling to hide in closets on the few occasions when factory inspectors would visit to check on working conditions in the mill.

The system of “helpers” was another way mill owners got around child labor laws. Very small children as young as 6 or 7 years old would visit the mill to bring meals to their parents or older siblings during the work day or simply to play amidst the machinery. These young “helpers” would begin to learn the jobs that older workers performed and try their hand at various tasks. The presence of tiny children in the mill could be explained to inspectors by saying the children were only “helping” and not on the payroll. As they got older, they spent more and more time helping until they began working full-time in the mills, usually between ages 10 to 14.

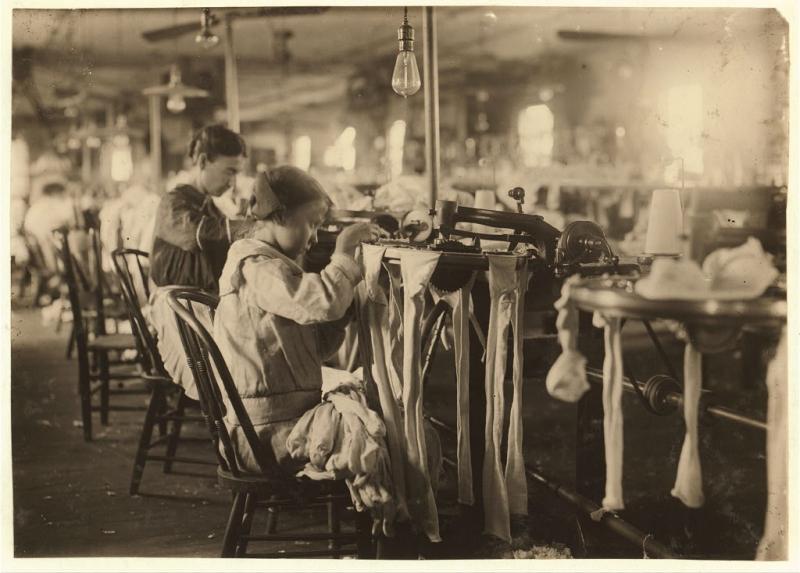

Many young mill laborers worked in the spinning room because mill owners felt their small hands were well-suited to this work. Work in the spinning room was not especially skilled or difficult, but required a watchful eye. Spinners were usually preteen or teen girls, who had to constantly attend to the cotton being spun on machines. These were the workers who “put up ends”, or repaired breaks in the thread. Doffers, often small boys, walked back and forth in the spinning room, replacing the full bobbins of thread with empty ones. Sweepers, also small boys, swept up the cotton fiber and lint from the floor and machinery to keep things running smoothly. Spinners and doffers were usually required to keep up with a certain number of machines on a side, and many workers remember“running sides” or being paid by the number of sides they worked.

Many former child workers speak of their eagerness to earn money, which pushed them to drop out of school and begin working in the mill. Some even began working against their parents’ wishes. It was difficult for some to see the advantage in continuing their schooling when recruitment ads claimed they could make as much as adult mill workers. Workers under 16 usually began working for 25 to 50 cents per day during the early 20th century, and could increase to $1.50 per day or more as they became more experienced.

For the child workers, working in the mills wasn’t always uninterrupted drudgery. Children were allowed to take breaks when their work was caught up, and some of the less strict supervisors let them go outside to play during breaks. The child workers were also allowed to talk to one another in the mill across the openings in the machinery. Sometimes, the workers learned how to read lips because the machines were so loud they couldn’t understand each other otherwise!

Workers in the mills also played pranks on each other. Frank Durham remembered workers teasing new employees who had just moved from the farm and didn’t know much about mill work. “There was something like that going all the time, some little old tricks and then playing pranks,” said Durham. “A new hand would come in down there sometime to work, and they’d send him after a left-handed monkey wrench, or go down there and get the key to the elevator, or the bobbin stretcher and all that stuff. Somebody that didn’t know there was no such thing.”