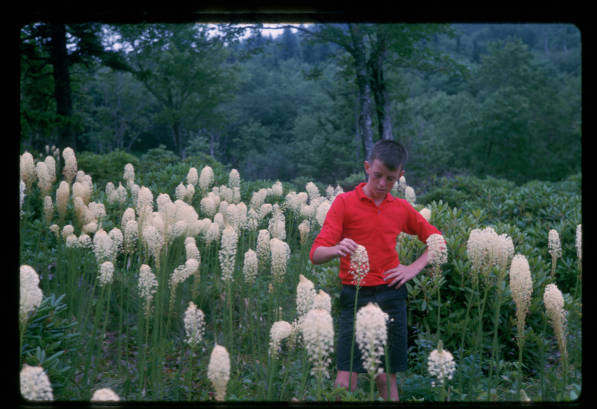

Hugh Morton took many photographs over his long life, and a large number of them are of natural scenes, wildlife, wildflowers, and trees. To those who knew Hugh from the more public and traditionally newsworthy of his activities and interests, his nature photographs may seem inconsequential or even incongruous, but they represent an intrinsic and important part of his life's interest and life's work. The photographs themselves tell the story: a waterfall on a Pacific island from his military days, maritime forests and plants near Wilmington, family members standing amidst meadows of wildflowers, ferns on vacations in Alaska and Hawaii, detailed shots of an individual flower, and, of course, the unique scenery and plants of his beloved Grandfather Mountain. Clearly, this was a man with a lifelong enjoyment of the natural world and its beauties. In later years, Hugh Morton's vocation was Grandfather Mountain, and he came to focus his lens increasingly on the special plants, animals, and scenery of that place. Many of the other themes of his life became similarly focused on and interwoven with "the mountain" -- politics, public service, family, entrepreneurship, Carolina sports, conservation, Scottish heritage, and more -- but perhaps no other of his varied interests and passions was so centered on Grandfather as his love of nature and passion for its conservation.

Grandfather Mountain is one of those places that immediately rises to the top of any list of important conservation areas, whether one's criteria emphasize plants, animals, natural communities, diversity, rarity, uniqueness, recreational opportunities, scenery -- whatever. The two historical signs flanking its entrance stand as sentinels of the importance and uniqueness of Grandfather Mountain's plants and animals. They honor the late 18th century explorations of French botanist André Michaux, and the mid 19th century visit by the most renowned American botanist of his generation, Asa Gray (for whom the rare and endangered Gray's Lily, Lilium grayi, is named). Upon his visit in August of 1794, Michaux was so enthused by the place and its plants that we may forgive (and enjoy!) his exemd hyperbole: "reached the summit of the highest mountain in all of North America, and with my companion and guide, sang the Marseillaise and shouted 'Long live America and the Republic of France, long live liberty!'"

If one made a list of the places with the greatest concentrations of unique and imperiled plant and animal species in eastern North America, Grandfather Mountain would be at or near the top of the list. Blue Ridge Goldenrod (Solidago spithamaea) occurs only on the high elevation cliffs of Grandfather, Roan Mountain and Hanging Rock Ridge, with perhaps 90 percent of its entire population on Grandfather Mountain. Bent Avens (Geum geniculatum) is similarly limited in distribution, and has the majority of its population on brookbanks and seeps in coves descending the flanks of Grandfather. Heller's Blazing-star (Liatris helleri) and Mountain Bluets (Houstonia montana) occur on a few apitional peaks, but also are considered to have their strongholds on Grandfather Mountain. Grandfather also serves as a southern refugium of arctic and boreal plants, such as Deerhair Bulrush (Trichophorum caespitosum), abundant in the arctic tundra of Alaska, Canada, Siberia, and Scandinavia, and found rarely as far south as the Adirondack Mountains of New York -- from whence it jumps to a dozen peaks in North Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, and South Carolina. On Grandfather it is a conspicuous cliffs and rocks along the summit ridge, notably in the area near the Swinging Bridge, forming dense grassy tussocks, moving stiffly in the nearly constant wind, green in summer and turning the tawny of deer hair in the fall and winter. Punctatum Rhododendron (Rhododendron minus) and North Carolina endemic Pinkshell Azalea (Rhododendron vaseyi) paradoxically reach their northernmost populations at Grandfather, being found more characteristically in the vicinity of Highlands, North Carolina, near the North Carolina/South Carolina/Georgia tricorner.

I first came to know Hugh in the late 1980s and early 1990s. I worked at the time as a botanist, ecologist, and conservation planner for the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program, a small state agency with the responsibility to catalog and help conserve the state's biological diversity of imperiled plant and animal species, high quality natural communities (forests, glades, dunes, marshes, etc.), and intact landscapes. Hugh was always proud of his "private enterprise approach" to conservation, but he did not hesitate to afford himself of services that federal agencies, state agencies, and private conservation organizations could provide him, and he frequently involved personnel from the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, North Carolina Natural Heritage Program, North Carolina Botanical Garden, or The Nature Conservancy when issues arose on the mountain. At this time, Hugh was already beginning to give conservation easements on portions of the Grandfather Mountain "backcountry" to The Nature Conservancy, and the building of new trails such as the Profile Trail required careful routing to avoid impacts to delicate seeps and populations of rare plants. I became involved in advising Hugh and his staff about the construction of the Profile Trail and other projects.

Soon after, news stories appeared about a plan to develop a 900 acre tract, known as the "Wilmor" tract, on the northwest side of Grandfather Mountain from Highway 105 up to the upper slopes of the mountain, at about the 5000 foot contour. Critical media coverage and the creation of a citizens' group opposed to the development soon followed. I and fellow biologist Mike Schafale were brought in by Hugh and The Nature Conservancy to assess the ecological significance of the tract; we found that many of Grandfather Mountain's hallmark imperiled species were abundant over all but the lowest portions (perhaps 100 acres of the total). The issue and its eventual solution provide a "view to Hugh." His friend and business partner, John Williams, owned a controlling interest in the 900 acres, and Hugh felt a personal loyalty to assure his friend of a financial return on his holding. In my conversations with him, Hugh clearly felt angry about the public criticism of his plans and its portrayal of the proposed development as a betrayal of the mountain; he defended the development as being "on the slope, not on Grandfather Mountain."

But he also clearly felt uneasy and conflicted about the potential development, and over the following year a solution was crafted that involved limited development of a shopping center at the lowest elevations, and permanent conservation of the 800 ecologically significant acres through a combination of donation and bargain sale to The Nature Conservancy, made possible by conservation donors. Through a complicated mix of politics, personal relationships and connections, science, conservation, public relations, entrepreneurship -- everything ended up pretty much all right.

Hugh's genuine interest in rare plants and their conservation can be seen in many other of his activities, about which there is space only for brief mentions. The Nature Museum on Grandfather has excellent, extensive and beautiful interpretation about rare plants and the threats to them. Hugh was an early supporter of the North Carolina Botanical Garden and its plant conservation mission, and chaired the Botanical Garden Foundation. The conservation of such an important site as Grandfather Mountain for many decades through purely private management is almost unique, and it is one of very few (and perhaps the only) United Nations Biosphere Reserves worldwide designated on primarily private property.

Grandfather Mountain is an amazing and unique botanical treasure, and the conservation, beauty, and biodiversity of that mountain is now forever associated with Hugh MacRae Morton. What a fortuitous confluence of a person and a place that proved to be!

You can see a collection of Hugh Morton's photographs here.