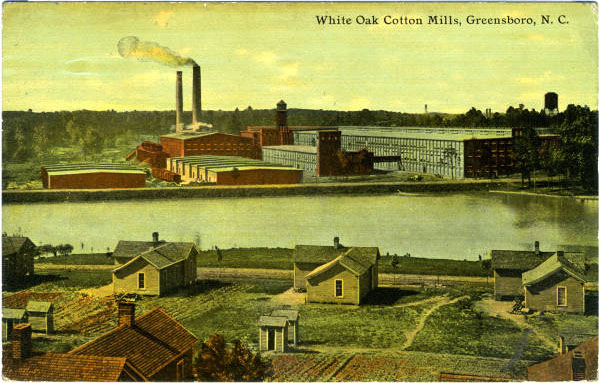

By 1900, a full 92 percent of textile workers lived in mill villages owned by the companies that employed them. Usually, the mill village included a supervisor's home, houses for workers and their families, one or more churches, a school, and the company store. In the early 1900s, most mill houses were one-story, four-room affairs, lit by kerosene lamps and heated by open fireplaces. Workers drew water from common wells and pumps, and less than 7 percent of mills in 1907-1908 had sewer facilities more elaborate than simple privies. Many manufacturers had a rule that required families to supply one worker for each room occupied, further encouraging the entry of children into the mills.

The closeness to the factory had its advantages for millhands, but it also meant that mill managers could keep close tabs on their employees, sometimes using supervisors or mill village policemen for surveillance. Mills often supported the churches in the villages, paying the salaries of ministers or providing maintenance and heat for the buildings, and, in turn, the donations from mill owners frequently shaped the message from the pulpit. Not surprisingly, some company-supported pastors preached a gospel that favored the company's interests.

Mills also sponsored village schools, sometimes providing buildings and paying teachers’ salaries. Supervisors would often send for children in the school when extra workers were needed in the mill. "Owners had little to gain by enforcing school attendance, since children who became ensnared by the factory at an early age were less likely to seek employment elsewhere as adults. These conditions improved only in the mid-1910s after schooling was made mandatory for all children under twelve years of age. By 1925 North Carolina's mill schools enrolled an average of 79 percent of all thirteen-year-olds, as compared to 83 percent for rural schools and 88 percent for city schools." (p. 128) Most mills provided the first seven grades of education free of charge, but workers would often have to pay for any schooling beyond that, meaning that most children went straight from the seventh grade into mill work.

Mills operated company stores and often sponsored a variety of other small businesses such as barber shops and pool halls. Those establishments were a convenience to workers, but they could also serve to keep millhands in debt to their employers. Mills also provided social workers, recreational activities, clubs, and educational opportunities, in part to provide better living conditions to their employees, but also to make sure that, in a time of labor shortage, millhands were satisfied enough that they would not seek employment elsewhere. Mill owners also hoped that the benefits they supplied to employees would silence critics from outside the mills who worried about poor working and living conditions, child labor, and mill village poverty. The results, however, were often disappointing. For their part, mill workers recognized that the sewing clubs, nurseries, and baseball teams offered by the companies were intended to keep them docile and loyal. Some workers refused to participate or created their own recreational activities as alternatives to company-sponsored options. Still others took part in the programs but did not buy into the company's intended message. They demanded higher pay and better conditions even as they took full advantage of the clubs and other activities.

Company "welfare work" failed to produce dramatic results because workers drew on the strengths of their own communities to avoid dependence on their employers. Millhands brought remnants of their lives on the farm with them and insisted on having gardens, barns for their animals, and chicken coops in the villages. They socialized together, often gathering for music and dancing, and helped their neighbors during difficult times, just as many had done in rural communities. Mill workers also created their own alternative churches and held emotional revivals that worried many mill owners.

"Viewed from the outside, mill villages seemed to deny workers the most basic forms of self-expression. But in muddy streets and cramped cottages cotton mill people managed to shape a way of life beyond their employers' grasp. Millhands' habits and beliefs were more than remnants of a rural past; they were instruments of power and protection, survival and self-respect, molded into a distinctive mill village culture. Sometimes that culture simply defended workers against condescension and economic hardship. At other times, it bred a spirit of independence that threatened the village's purpose as an institution of labor control. In either case, it offered assurance that mill folks were 'fine, honest, hard-working people.'"

Source Citation:

Leloudis, James and Kathryn Walbert. "Life in the Mill Villages." Originally published in "Like A Family," http://www.ibiblio.org/sohp/laf/factory.html#life.