Valdese, NC

A History

By Fred Cranford

Reprinted with permission from the Tar Heel Junior Historian, Spring 2006.

Tar Heel Junior Historian Association, NC Museum of History

In the year 1184, and again in larger numbers in 1485, people who became known as Waldenses fled from southern France and the Piedmont region of Italy into the towering Cottian Alps between those two European countries. (In French, the name Waldenses means “People of the Valleys,” because this group lived in the deep valleys between mountain ridges that fanned out like fingers on a hand from the northern Italian city of Turin.) They fled to the Alps to escape religious persecution. But the rulers of France and Italy and leaders of the Roman Catholic Church pursued them. They branded the Waldenses as heretics because of their belief that common people should be allowed to read and interpret the Bible.

In the year 1184, and again in larger numbers in 1485, people who became known as Waldenses fled from southern France and the Piedmont region of Italy into the towering Cottian Alps between those two European countries. (In French, the name Waldenses means “People of the Valleys,” because this group lived in the deep valleys between mountain ridges that fanned out like fingers on a hand from the northern Italian city of Turin.) They fled to the Alps to escape religious persecution. But the rulers of France and Italy and leaders of the Roman Catholic Church pursued them. They branded the Waldenses as heretics because of their belief that common people should be allowed to read and interpret the Bible.

Over the next five hundred years, French and Italian armies launched thirty-five massive invasions into those valleys, intent upon eliminating the Waldenses as a people. The end result was exile in Switzerland. Then, in 1689, a determined band of nine hundred Waldenses fiercely fought their way across the Alps to regain their homeland. Persecutions ceased. But the Waldenses were treated as second-class citizens until 1848, when King Charles Albert—King of Sardinia and Duke of Savoy, which included the Waldensian valleys—granted them full civil liberties and freedom of conscience.

Decades of peace brought another crisis. During the years of persecution, violent deaths, famine, and disease had reduced the number of Waldenses. But when the massacres ended, population in their valleys grew rapidly. For generations, their small farms had been divided and redivided as children grew to adulthood, until tillable plots became too small to divide further. No longer could they grow enough food to feed their families. People were starving.

Hopelessness did what hundreds of years of persecution could not: It forced many of the younger Waldenses to leave their beloved valleys. Reluctantly, hundreds emigrated to Uruguay, Brazil, and Argentina in South America. Others moved to Missouri and Utah in the United States. The largest immigrant group, though, settled in what became Valdese, North Carolina.

From North Carolina had come a seemingly generous offer. The president of the Morganton Land and Improvement Company learned from an aunt traveling in Europe that the Waldenses were interested in finding land in America. The company contacted Waldensian pastoral leaders in the valleys with an enticing proposal. On credit, the company would sell a single tract of a hundred thousand acres in western North Carolina, enabling a large group of Waldenses to remain together. Seeing this proposal as an answer to their prayers, in March of 1892 the Waldenses sent two farmers, Jean Bounous and Louis Richard, to examine the land. Both men quickly agreed that the first land offered was too mountainous for farming. They refused this offer but had the company show them other smaller tracts. Finally, in Burke County, between Morganton and Connelly Springs, they found a tract of ten thousand acres that Bounous thought “showed promise.” Richard disagreed. Nevertheless, Bounous sent a telegram to Italy saying, “The land is good.”

Desperate in their suffering, hundreds of Waldenses walked many miles over mountainous paths from distant valleys to hear the two men’s report upon their return from America. Not until this meeting, however, did the people learn that the two men disagreed on the merit of the land. Tears filled the eyes of many as they listened to the conflicting opinions, for some had already sold their farms. “It is no Canaan,” Bounous said. “But if there are those of you who are not afraid of work—hard work—you can have a farm the size of this whole valley.” Dr. Charles Albert Tron, president of the Waldenses’ Emigration Committee, called for the decision that had to be made: “How many will go in spite of the unfavorable report?” Slowly, reluctantly, a few hands raised. Twenty-nine people committed to depart for North Carolina in the spring of 1893. A second group of 179 would leave in the fall, and others, later on.

These frightened but determined emigrants shared steamship steerage quarters with other poor passengers who also hoped to escape the hardships of Europe for a brighter future in America. The Waldenses’ future looked brighter than most, for they could proudly say, “We have land in North Carolina.”

When the Waldenses arrived in America, the Richmond-Danville Railroad Company carried them from Norfolk, Virginia, to North Carolina free of charge. The steam-engined train stopped literally “in the middle of nowhere” just long enough to unload the eleven men, five women, and thirteen children with their luggage—no train station, no town, and only one house in sight. On hand to greet the immigrants were members of the Morganton Land and Improvement Company and their families. Watching from a nearby hillside was a small band of curious locals, who would be the closest neighbors to these “furriners” who, they had heard, spoke French, Italian, and a dialect called “Patois” but not a word of English.

Once all were safely off the train, Dr. Tron led the Waldenses in a prayer of thanks for a safe journey and the opportunities awaiting them. The only one of the group, in fact, who spoke English, he would be with them just a few weeks before returning to Italy to ready the next group. Surrounded by acres of uncleared woodland, these twenty-nine people faced a daunting task: to provide lodging and food for the 179 others who would arrive in November.

Prior to the Waldenses’ arrival, the Morganton Herald wrote, “This Waldensian Colony, the first foreign settlement in the state of any importance since the Moravian settlement at Salem, is we hope the precursor of many such movements.”

The contract with the Morganton Land and Improvement Company called for a corporation governed by a board of directors comprised of Waldenses and members of the land company. It also established, at the insistence of company officials in order to protect their investment, “a system of life in common for all members of the colony, each sharing the burdens, the interests, the duties, and the privileges.” This “share and share alike” communal approach seemed to the land company a fair way for immigrants to succeed in making a new life in America.

Excitement was high as the Waldenses chose the name for their colony, Valdese (an Americanization of “Valdesi,” Italian for “Waldenses”). During the first tour of their land, however, the excitement over owning large farms quickly disappeared. In their former country, all the homes were tightly clustered in villages, surrounded by farmlands and pastures. Here families would live on separate farms, the nearest neighbor over a mile away. Accustomed to living near one another, they were shocked to find themselves so isolated from other families.

To earn money to provide food, produce boards to build houses, and pay for the land, the men worked at a sawmill furnished by the land company. For each day worked, a man earned forty cents’ credit at the corporation store. The saw was powered by an old steam engine requiring constant repairs—quite a challenge for farmers who had never seen a sawmill! Some could keep it repaired and running; others could not. Yet the corporation’s shared community policy required that each man take a turn operating the saw, as well as cutting and hauling logs. The situation fueled temper flare-ups and occasional fistfights when inept machinists had charge of the saw.

The corporation also contracted with a Charlotte company to open a hosiery mill in Valdese that would employ only Waldenses, to help them become financially stable. But, like the sawmill, the hosiery mill was set up with old, manually operated machinery needing much repair. On good days, machine operators earned ten to fifteen cents. And defective products from faulty machinery had to be mended. Women and children learning those tasks made as little as three cents a day.

Little wonder that barely eighteen months after arriving, the Waldenses abandoned the idea of holding the land “in common.” The “share and share alike” philosophy had not worked. After bargaining, officials of the land company agreed to take back all the land and sell smaller farms of forty to eighty acres to individual families.

Waldenses in Valdese found the land poor and rocky. But eventually, a church, houses, stores, and a school replaced rocks and stumps. Farming continued as it had in their homeland. Production from the sawmill increased, providing lumber for local construction and shipment by railway to other markets. While the hosiery mill was a “veritable sweatshop,” that on-the-job training led to the development of their own mills. Their experiment in shared community living failed. They admitted that failure, dissolving the Valdese Corporation in favor of free enterprise. Afterward, they worked just as hard. Most, in fact, worked harder, for the fruits of their labors were their own. The land they cleared was theirs to pass on to their children.

Together the Waldenses built the Valdese that became known by 1938 as the “Fastest Growing Town in North Carolina.” The 1893 colony of less than three hundred settlers became an industrial town of 4,600, still thriving today—with tourism supplementing industry as the economic focus.

At the time of the publication of this article, Fred Cranford, a retired educator, served on the board of directors of the History Museum of Burke County and the Waldensian Trail of Faith in Valdese. He is the author of From This Day Forward, the outdoor historical drama that tells the story of the Waldenses each summer at the Old Colony Amphitheater in Valdese.

Additional Resources:

Visit Valdese: http://www.visitvaldese.com/

American Waldensian Society: http://www.waldensian.org/

NC Historical Marker: https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-highway-historical-marker-program/

Image Credit:

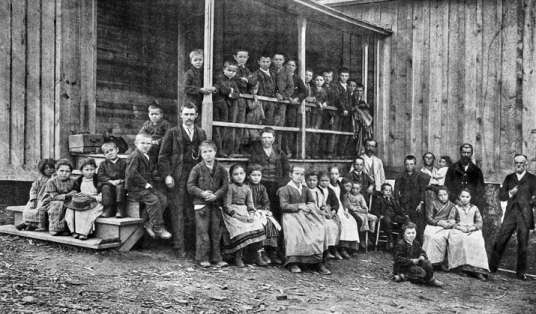

Waldensian schoolchildren and teacher (standing beside steps) at Valdese, ca. 1905. North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Library.

1 January 2006 | Cranford, Fred