Bluegill

Lepomis macrochirus

Written by Brad E. Hammers and Shari L. Bryant

Updated by Keith Ashley, fisheries biologist

North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, 2010

Classification

Class: Osteichthyes

Order: Perciformes

Average Size

Length: 3 to 5 in. up to 10 in.

Weight: 2 to 4 oz. up to 4 lbs.

Food

Zooplankton, aquatic insects and small fish. Also snails, mollusks, mites, fish eggs and plants.

Spawning

The spawning season for bluegills usually begins around May and continues through October. Eggs usually hatch within 1 or 2 days depending on water temperature.

Young

Newly hatched bluegills are called fry. A pair of bluegills can produce from 2,000 to 10,000 young. The fry begin to swim within a short time. Males protect the fry for several days after hatching.

Life Expectancy

The maximum life span for the bluegill is 8 to 10 years.

Range and Distribution

Range and Distribution

Originally, the bluegill ranged throughout much of the eastern half of the United States. They are still found in every county in North Carolina. Introductions of this fish have extended their range to the western part of the country to include every state except Alaska.

General Information

Commonly referred to as “brim” or “bream,” the bluegill is the most common of all the sunfishes. It is a member of the sunfish or pan fish family, which also includes the crappie and largemouth bass. Other species of sunfish sometimes mistaken for bluegills are redears, pumpkinseeds and warmouths. Because it is one of the true sunfish species that grow large enough to be acceptable to fishermen, the bluegill has introduced many people to the sport of fishing. Its size, coupled with its tenacious fighting ability and voracious appetite, make it a favorite of many anglers.

According to a recent statewide survey, the popularity of sunfish fishing ranks behind only largemouth bass and crappie angling.

Description

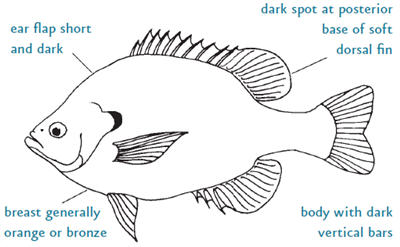

Bluegills are characterized by a small head and mouth and a hand- or pan-shaped body. The body is often an olive-green color with several broad, dark vertical bars on the side. The throat and belly are often yellowish or orange in color. The lower jaw and gill color is powder blue, hence the name “bluegill.”

There is a black blotch at the base of the dorsal (top) fin. The earflap is entirely black, helping to distinguish the bluegill from other sunfish species that often have an orange or red spot on the earflap.

Bluegills tend to breed with other sunfish species, resulting in hybrids with the external characteristics of both parents. In populations where hybridization occurs, identification is often difficult.

History and Status

Bluegills are a highly adaptable species native to North Carolina that can be found in streams, rivers, ponds, lakes and reservoirs throughout the state. They prefer warm slow-moving or still water, usually close to aquatic vegetation, but flourish in Piedmont farm ponds and in ponds and slow moving rivers in the Coastal Plain. Because of their prolific nature, bluegills are not considered threatened or endangered in North Carolina.

Habitat and Habits

Habitat and Habits

Bluegills prefer protected areas with clear, quiet water and a bottom covered with sand, gravel or mud. Warm, shallow, lakes or ponds support the largest populations, but they can also be found in slow-moving streams and rivers. Bluegills are capable of spawning once per month from April through October with the peak spawn occurring between May and June when water temperatures reach about 70 degrees F. Bluegills usually mature at 1 to 2 years of age and begin to spawn when they reach 2 to 3 years. Males select the nest site and create a nest 1 to 2 ft. in diameter by fanning the bottom of the lake or river with their tail to form a shallow depression. Nests are usually located in 1 to 6 ft. of water. Often, several nests will be located within the same area because spawning bluegills tend to form nesting colonies. The female will lay 2,000 to 60,000 adhesive eggs in a nest with the eggs hatching within 1 to 2 days, depending upon the water temperature. During this time, the male guards the nest, protecting the eggs and the hatched young from predators.

The bluegill is a prey species and therefore its reproductive rate and frequency is higher than that of a predator species such as the largemouth bass. If predation on bluegill is low, their numbers can become greater than what the habitat of a pond or small lake can support. When this happens, food becomes scarce, growth slows, populations become stunted, and fish rarely, if ever, reach a harvestable or desirable size. The current world record bluegill is 15 in. long, 4 lbs., 12 oz. Bluegills eat mainly aquatic insects, zooplankton and small fish; however, they may also consume aquatic vegetation, snails or fish eggs. Because of their small mouths, they can only eat small minnows or the young of other fish. Bluegills tend to swim in schools and occupy shoreline habitats 1 to 20 ft. deep. The schools are usually located near some type of shelter such as docks, weedbeds or bridges. Larger bluegills usually occupy deeper areas and are often loners.

People Interaction

Natural mortality in bluegills is high but angling can also contribute significantly to mortality, especially in small farm ponds. Bluegills normally have a lifespan of 4 to 6 years but fish up to 11 years are known. They are a highly sought-after game fish and provide excellent fishing opportunities, particularly in small ponds and coastal rivers throughout North Carolina. Bluegills are most active in early morning or late afternoon and can readily be caught during these times. The schooling nature of the bluegill can make for some fast and furious fishing.

NCWRC Interaction: How You Can Help

The N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission provides free public fishing opportunities at more than 100 public fishing areas and community fishing sites throughout the state. The Commission has cleared banks of underbrush, and in some cases, constructed fishing piers, graveled or paved parking lots, installed fish attractors or baited the areas with fish feed. The Commission enhances fishing at many community sites by stocking harvestable-sized fish from April to September. We also loan fishing tackle to the public the way a library loans books! You just register at community parks that participate in the Tackle Loaner Program to receive a tackle loaner ID card and that allows you to check out a rod and reel for the day. To find public and community fishing sites near you, and tackle-lender locations, visit the Wildlife Resources Commission Web site, www.ncwildlife.org and click on “Fishing”, or call the Division of Inland Fisheries at (919) 707-0220. Maybe you will catch a bluegill!

References:

Eddy, Samuel and James C. Underhill. How to Know the Freshwater Fishes (Iowa, 1980).

Jenkins, R.E. and N.M. Burhead. Freshwater Fishes of Virginia. (American Fisheries Society, Maryland, 1993).

Menhinick, Edward F. The Freshwater Fishes of North Carolina (North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, 1991).

Rohde, F.C., R.G. Arndt, D.G. Lindquist, and J.F. Parnell. Freshwater Fishes of the Carolinas, Virginia, Maryland and Delaware. (The University of North Carolina Press, 1994).

Tomelleri, Joseph R. and Mark E. Eberle. Fishes of the Central United States (University Press of Kansas, 1990).

Sternberg, Dick. The Compleat Freshwater Fisherman (Cy DeCosse Incorporated, 1987).

Credits:

Illustration by J.T. Newman. Photos by North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission.

Produced by the Division of Conservation Education, Cay Cross–Editor.

11 June 2010 | Ashley, Keith; Bryant, Shari L. ; Hammers, Brad E.