Iron and Steel Industry

The search by European settlers for sources of iron in North Carolina began with the earliest explorations. Members of Sir Walter Raleigh's first expedition to Roanoke Island and the Chowan River Valley in 1585 reported two iron ore discoveries. Over time, three localities with substantial iron ore deposits were to play a modest role in the economic history of the state. These were the Deep River deposits in Chatham County, the deposits centered around the Big Ore Bank in Lincoln County, and the substantial magnetite ore deposits in Avery County. However, no significant refining in North Carolina was to occur for almost two centuries after the initial sixteenth-century discoveries.

The search by European settlers for sources of iron in North Carolina began with the earliest explorations. Members of Sir Walter Raleigh's first expedition to Roanoke Island and the Chowan River Valley in 1585 reported two iron ore discoveries. Over time, three localities with substantial iron ore deposits were to play a modest role in the economic history of the state. These were the Deep River deposits in Chatham County, the deposits centered around the Big Ore Bank in Lincoln County, and the substantial magnetite ore deposits in Avery County. However, no significant refining in North Carolina was to occur for almost two centuries after the initial sixteenth-century discoveries.

As part of the effort to maintain the British colonies in North America as economic dependencies unable to compete with home industries, the British Parliament passed an act in 1750 that prohibited the manufacture in the colonies of any iron product except pig iron and bar iron, which had not yet been forged into useful implements. As relations between the Crown and the American colonies deteriorated, the colonial legislature resolved to encourage the development of a native iron industry. In 1775 the North Carolina Provincial Congress offered a bounty for the establishment of the first colonial iron forge. At the end of the same year the Provincial Congress rented the furnaces and iron forges built by John Wilcox at Ore Hill near the Deep River iron ore deposits in Chatham County in order to supply iron cannons and cannonballs for the revolutionary forces. Operations were greatly hindered by the lack of well-trained, experienced workers, and the enterprise collapsed before any substantial armaments were produced. Congress surrendered its interest in the works to Wilcox in 1777. The structures were heavily damaged by a storm in 1780 and were abandoned.

Farther west in Lincoln County, some of the state's most important bloomeries and forges were successfully established. This region possessed all the necessary resources: a rich and substantial iron ore deposit, hardwood trees to produce charcoal fuel, limestone to extract the impurities from the metal, refractory crystalline rock to build the furnaces, and falling water to power the bellows and heavy hammers of the forges. Equally important, this region was settled by Germans and Ulster Scots, many of them trained craftsmen, who established Lincoln County as a major industrial center in North Carolina during this period by founding the iron and textile industries.

The impetus for the development of iron manufacturing in Lincoln County was the passage in 1788 of "An Act to Encourage the Building of Iron Works in this State" by the North Carolina General Assembly. The act provided a ten-year tax exemption and a grant of 3,000 acres of land (unfit for cultivation, to be used as a source of trees for charcoal) to anyone who built an operating iron forge. Within a decade, a number of family-owned forges were in operation in Lincoln County. In 1789 Peter Forney and several associates obtained the Big Ore Bank property and began to exploit its substantial iron ore deposits. John Fulenwider built and operated forges at two locations beginning in 1804. Pig iron produced in the furnaces was forged into a wide range of products for neighboring towns and farms, including plows, horse shoes, wagon tires, chains, nails, tools, muskets, and kitchen implements. Iron products and bar iron were sometimes used as a medium of exchange. During the War of 1812, cannonballs cast at Fulenwider's High Shoals Iron Works were shipped by flatboats to Charleston.

The peak production of pig iron was achieved in 1830, when 1,800 tons of the metal was refined. The skilled iron workers of Lincoln County used this iron to fabricate items as simple as kitchenware and as sophisticated as clocks, steam engines, and farm machinery.

The peak production of pig iron was achieved in 1830, when 1,800 tons of the metal was refined. The skilled iron workers of Lincoln County used this iron to fabricate items as simple as kitchenware and as sophisticated as clocks, steam engines, and farm machinery.

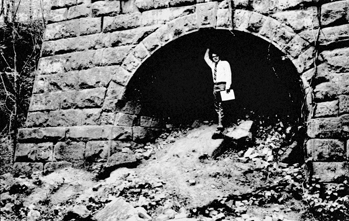

At the outbreak of the Civil War, 49 ironworks were known to be active in the state, mostly in Lincoln, Cherokee, Cleveland, Surry, and Cumberland Counties. When the Confederacy lost its access to northern iron manufacturers, efforts were made to invigorate the iron industry in North Carolina. In 1861 the Sapona Iron Company built a furnace at Ore Hill (now known as Mount Vernon Springs) in Chatham County on the site of John Wilcox's eighteenth-century ironworks, operating it throughout the war. George Lobdell and J. M. Heck, founders of the Cape Fear Iron and Steel Company, operated the Endor Furnace near the Deep River in Lee County beginning in 1862. Iron ore was transported by boat from nearby mines to the furnace. The resulting iron stock was shipped to Fayetteville, where railroad wheels were fabricated. In February 1865 the Congress of the Confederate States passed a bill to build a foundry and arsenal in the Deep River Valley. Construction began but was ceased when the war ended.

The iron industry in North Carolina fared poorly in the face of northern competition following the end of the Civil War. The maturation of iron-making operations in nearby states such as Virginia and Tennessee, as well as the expansion of works in New York and Pennsylvania, combined to ruin the promise that North Carolina's ironworks had shown during the early and mid-nineteenth century. After the Civil War, the abolition of free, enslaved labor and the emancipation of enslaved people further deteriorated the ironworks industry. Substantial deforestation also played a role in the decline, particularly in Lincoln County, where the small furnaces operated intermittently or closed down.

Another chapter in the history of the North Carolina iron and steel industry occurred in Avery County. The presence of magnetite iron ore in the western mountains was first noted by Reuben White in about 1780. In 1826 Joshua Perkins and two of his brothers took advantage of the General Assembly's 1778 act to build a forge and a dam at the Cranberry iron deposit. The first underground tunnels were driven into the vein in 1882, and a small blast furnace was constructed at the site to smelt the low-titanium ore. In that same year the East Tennessee & Western North Carolina Railroad began to run ore trains from Cranberry to Johnson City, Tenn., where the Cranberry Furnace Company later operated a larger blast furnace. In the first two decades of the twentieth century, annual iron shipments from Cranberry to Johnson City ranged from 50,000 to 100,000 tons. Mining at Cranberry continued until about 1940.

Since the early years of the twentieth century, numerous metal fabricating businesses have operated in North Carolina, manufacturing a wide range of finished iron and steel products. The starting materials utilized by firms such as Charlotte's Nucor Corporation have been refined iron and steel stock purchased from mills located outside of the state.

References:

W. S. Bayley, Magnetic Iron Ores of East Tennessee and Western North Carolina (1932).

Lester J. Cappon, "Iron-Making: A Forgotten Industry of North Carolina," NCHR 9 (October 1932).

Robert B. Gordon, American Iron, 1607-1900 (1996).

Additional Resources:

The First Provincial Congress. ANCHOR. https://www.ncpedia.org/anchor/first-provincial-congress

Minutes of the Provincial Congress of North Carolina, August 25, 1774 - August 27, 1774, Volume 09, Pages 1041-1049: https://docsouth.unc.edu/csr/index.html/document/csr09-0303.

"Iron Works." NC Highway Historical Marker O-9, NC Office of Archives & History: https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-highway-historical-marker-program/Markers.aspx?sp=Markers&k=Markers&sv=O-9.

"Troublesome Iron Works." NC Highway Historical Marker J-16, NC Office of Archives & History: https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-highway-historical-marker-program/Markers.aspx?sp=Markers&k=Markers&sv=J-16.

"Wilcox Iron Works." NC Highway Historical Marker H-24, NC Office of Archives & History: https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-highway-historical-marker-program/Markers.aspx?sp=Markers&k=Markers&sv=H-24.

"Cranberry Mines." NC Highway Historical Marker N-6, NC Office of Archives & History: https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-highway-historical-marker-program/Markers.aspx?sp=Markers&k=Markers&sv=N-6.

"Endor Iron Works." NC Highway Historical Marker H-102, NC Office of Archives & History: https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-highway-historical-marker-program/Markers.aspx?sp=Markers&k=Markers&sv=H-102.

"John Fulenwider." NC Highway Historical Marker O-54, NC Office of Archives & History: https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-highway-historical-marker-program/Markers.aspx?sp=Markers&k=Markers&sv=O-54.

"Peter Forney 1756-1834." NC Highway Historical Marker O-61, NC Office of Archives & History: https://www.ncdcr.gov/about/history/division-historical-resources/nc-highway-historical-marker-program/Markers.aspx?sp=Markers&k=Markers&sv=O-61.

Iron Forging, NC Business History: http://www.historync.org/ironforging.htm

High Shoals, NC, Princeton: http://www.princeton.edu/~achaney/tmve/wiki100k/docs/High_Shoals,_North_Carolina.html

Remembering Avery County: Old Tales from North Carolina's Youngest County. By Michael C. Hardy, 2007. GoogleBooks.

Search results for 'Iron' in the E.S.C. Quarterly, North Carolina Digital Collections, Department of Cultural Resources.

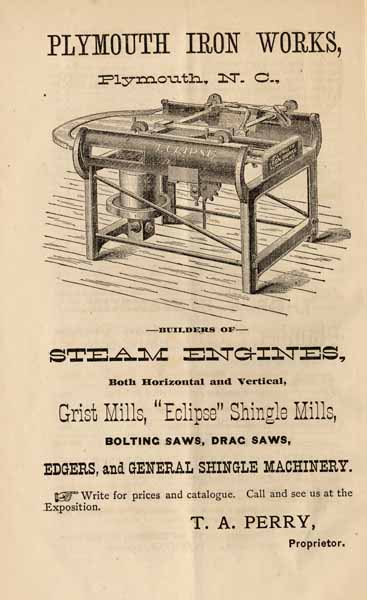

Image Credit:

Plans of Buildings, Rules and Regulations Governing Exhibitors at the North Carolina State Exposition: Raleigh, N.C., October 1st to October 28th, 1884: Also Premium Lists of the North Carolina Agricultural Society and the North Carolina Industrial Association: Electronic Edition. North Carolina State Exposition. https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/buildingplans/buildingplans.html.

The furnace opening at Endor Furnace, ca. 1970. Courtesy of North Carolina Office of Archives and History, call #: N_70_7_586-594 – Endor Iron Furnace, Lee County, 1970.

1 January 2006 | McKaughan, Joshua; Wait, Douglas A.