Cherokee

by William L. Anderson and Ruth Y. Wetmore, 2006.

Additional research provided by John L. Bell.

See also: John Ross

Part i: Overview; Part ii: Cherokee origins and first European contact; Part iii: Disease, destruction, and the loss of Cherokee land; Part iv: Revolutionary War, Cherokee defeat and additional land cessions; Part v: Trail of Tears and the creation of the Eastern Band of Cherokees; Part vi: Federal recognition and the fight for Cherokee rights; Part vii: Modern-day Cherokee life and culture; Part viii: References and additional resources

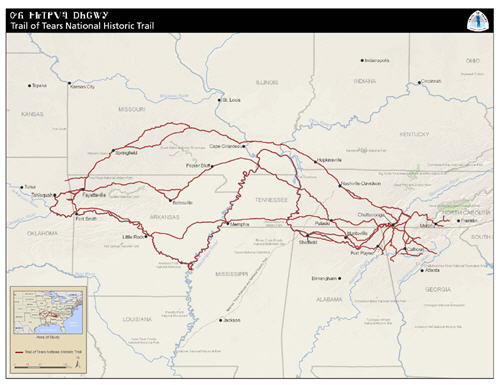

Part V: The Trail of Tears and the Creation of the Eastern Band of Cherokees

In 1830 Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, setting the stage for the forced removal of the Cherokee and the infamous Trail of Tears. In 1835, a small, unauthorized group of about 100 Cherokee leaders (known as the Treaty Party) signed the Treaty of New Echota (Georgia), giving away all remaining Cherokee territory in the Southeast in exchange for land in northeastern Oklahoma. Principal Cherokee Chief John Ross collected more than 15,000 signatures, representing almost the entire Cherokee Nation, on a petition requesting the U.S. Senate to withhold ratification of this illicit treaty. The Senate, however, approved the treaty by a margin of one vote in 1836. The treaty gave the Cherokee people two years to vacate their mountain homeland and go west to Oklahoma.

In 1830 Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, setting the stage for the forced removal of the Cherokee and the infamous Trail of Tears. In 1835, a small, unauthorized group of about 100 Cherokee leaders (known as the Treaty Party) signed the Treaty of New Echota (Georgia), giving away all remaining Cherokee territory in the Southeast in exchange for land in northeastern Oklahoma. Principal Cherokee Chief John Ross collected more than 15,000 signatures, representing almost the entire Cherokee Nation, on a petition requesting the U.S. Senate to withhold ratification of this illicit treaty. The Senate, however, approved the treaty by a margin of one vote in 1836. The treaty gave the Cherokee people two years to vacate their mountain homeland and go west to Oklahoma.

By May 1838, few Cherokees were prepared to move, so President Martin Van Buren, who had succeeded Jackson in 1837, dispatched federal soldiers commanded by Gen. Winfield Scott to round up Cherokees in North Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama and place them in various internment camps and stockades. The horrible conditions facing his people at these poorly planned facilities led Ross to appeal to the president for a delay in the removal until fall, when water and game would be more plentiful. Van Buren agreed, and between October 1838 and March 1839, the Cherokee moved west. The journey was mismanaged; there was a shortage of supplies; and the troops rushed the Indians onward, refusing to allow them to minister to their sick or bury their dead. Of the approximately 15,000 who began the trek, an estimated 4,000 perished.

Scott to round up Cherokees in North Carolina, Tennessee, Georgia, and Alabama and place them in various internment camps and stockades. The horrible conditions facing his people at these poorly planned facilities led Ross to appeal to the president for a delay in the removal until fall, when water and game would be more plentiful. Van Buren agreed, and between October 1838 and March 1839, the Cherokee moved west. The journey was mismanaged; there was a shortage of supplies; and the troops rushed the Indians onward, refusing to allow them to minister to their sick or bury their dead. Of the approximately 15,000 who began the trek, an estimated 4,000 perished.

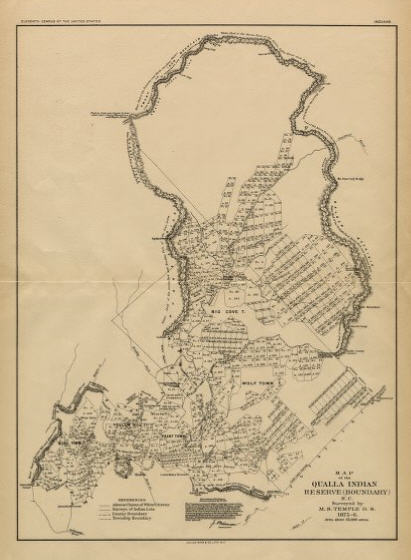

Approximately 300 to 400 Cherokees remained in North Carolina, hiding in the mountains. One of their leaders, Tsali, was captured and executed for killing two federal soldiers pursuing him and his family, but some of his followers and other Cherokees (who had possibly aided in Tsali's capture) were allowed to remain. Between removal of the Cherokee Nation in 1838 and the end of the Civil War, many Cherokees gave their money to William Holland Thomas, their agent and later their only white chief, to purchase land for them. Thomas acquired many of the tracts that would make up the modern-day Qualla Boundary, the official name of the Cherokee Indian Reservation in North Carolina. These Cherokees—together with the hundreds who had hidden in the mountains, who already legally owned land through the Treaty of 1817, or who had escaped the Trail of Tears and returned--formed the nucleus of what would become the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians.

Keep reading > Part VI: Federal recognition and the fight for Cherokee rights

Image credits:

"Map of Trail of Tears National Historic Trail," 2009. National Park Service, U.S. Department of Interior. Online at: https://www.nps.gov/trte/planyourvisit/directions.htm

U. S. Census Office. "Map of the Qualla Indian Reserve (Boundary) N.C.," 1890. ID: MC.183.C522.1876t. North Carolina Maps. Online at: http://dc.lib.unc.edu/u?/ncmaps,1055

1 January 2006 | Anderson, William L. ; Wetmore, Ruth Y.