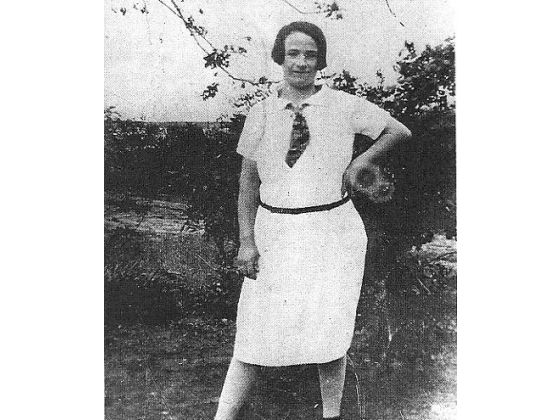

Wiggins, Ella May

By Mary E. Frederickson, 1996; Revised by SLNC Government & Heritage Library, June 2023

ca. Mar. 1900–14 Sept. 1929

Ella May Wiggins, textile worker, balladier, and union organizer, was born in the mountains of Cherokee County, near Bryson City, the daughter of James and Elizabeth Maples May. Her father, a lumberjack, was killed in a job-related accident when Ella May was a young girl, and she and her brother Wesley went to work in a nearby mill to help support the family. Trained as a spinner, she married a fellow mill employee, Johnny Wiggins, who, like her father, had worked in the timber region, and together they left the mountains to seek work in the burgeoning industrial region of Gaston County.

Ella May Wiggins, textile worker, balladier, and union organizer, was born in the mountains of Cherokee County, near Bryson City, the daughter of James and Elizabeth Maples May. Her father, a lumberjack, was killed in a job-related accident when Ella May was a young girl, and she and her brother Wesley went to work in a nearby mill to help support the family. Trained as a spinner, she married a fellow mill employee, Johnny Wiggins, who, like her father, had worked in the timber region, and together they left the mountains to seek work in the burgeoning industrial region of Gaston County.

Ella May and Johnny Wiggins settled in Bessemer City, where they both took jobs in the American Mill. Ten years later, at age twenty-nine, Ella May had borne seven children and been deserted by her husband. She sought work on the night shift in order to stay with her children by day. Money and food were scarce, and two of the children, suffering from malnutrition, developed rickets and died of respiratory infections. Living near her brother's family with a man named Charley Shope, Wiggins became the central figure in a network of family and friends to whom she looked for support. Her ties to the poor white and black families who lived near her developed into relationships that contradicted the rigid racial mores of the early twentieth-century South. Ella May understood the plight of southern black workers, for their lives mirrored her own situation. She came to realize that her future was inextricably bound to the collective destiny of those who lived around her, both black and white.

These stirrings in Ella May Wiggins's mind became more focused as economic and racial issues in the southern Piedmont gained public attention in the late 1920s. The leading textile county in the South, Gaston, formed the geographic center of the New South's textile industry. In twenty years, between 1909 and 1929, the number of mills in the county more than doubled until there were over one hundred in a ten-mile radius. Built with new equipment, these factories were caught in an economic squeeze brought on by declining markets and increasing prices of raw materials, machinery, and labor. Faced with a tightening economy, manufacturers began to change their operations in the late 1920s, initiating a series of layoffs and increasing the workload of weavers and spinners. Workers named the new system the "stretch-out," which, according to one North Carolina textile worker, meant: "They'd put more work on you for the same pay until the people couldn't stand it no longer." Employers in many mills not only increased hours but also reduced wages. But the margin between subsistence and starvation was already too narrow for most southern mill hands to tolerate a wage cut. Workers like Ella May Wiggins, struggling to support five children on $9.00 a week, faced a decrease in wages with disbelief, anger, and action.

Wiggins and other Gaston County workers, having suffered the effects of a stretch-out introduced during 1927–28, began to organize the fight for higher wages and better conditions during the spring of 1929. The Loray Mill in Gastonia, the county's largest employer with over 2,000 workers, became the focus of efforts by the National Textile Workers' Union (NTWU) to establish a southern stronghold. On 25 March five union members lost their jobs at the Loray Mill, precipitating a strike vote by 1,000 workers on 30 March. On 1 April close to 1,800 workers stayed out on strike, but the Manville-Jenckes Company, northern owners of the Loray Mill, refused to negotiate with the workers and ignored the NTWU demands for a minimum weekly wage of $20, a forty-hour week, equal pay for women, abolition of the stretch-out, and union recognition. On 4 April the state militia arrived to quell scuffles on the picket line; by 20 April many strikers had returned to work, the militia had withdrawn, and newly sworn local deputies enforced an ordinance against picketing. The union retained a loyal force of several hundred members who continued to picket in front of the five-story red brick mill and to win converts among those workers who had returned to work.

The strike at the Loray Mill engendered support from workers in nearby mills, and in early April 1929 Wiggins and fellow workers from the American Mill in Bessemer City staged a spontaneous walkout and joined the NTWU. The American Mill contingent helped sustain the Loray strikers, and Wiggins emerged from among the workers in Bessemer City as a strong leader. Described by one NTWU organizer as "a person of unusual intelligence," Ella May frequently led the singing among workers attending mass meetings at Loray. She seemed to understand each facet of the complex Gastonia situation and spoke to many groups of workers about the strike and the union, urging men and women alike to stand firm in their commitment. Most significantly, Wiggins sought cooperation between black and white workers. Independently, she organized a group of black workers, friends and neighbors who lived near her in Stumptown, a small community outside of Bessemer City, and brought them into the NTWU.

Events in the Gastonia strike escalated during the late spring and early summer. In mid-April a mob tore down the NTWU Gastonia headquarters building and raided the strikers' relief store. Ironically, the raid did not result in apprehension of members of the mob, but in the arrest of nine union men. Such an outrageous assault brought nationwide publicity for the strikers, the denunciation of the raid by southern liberals, and increased relief contributions from across the country. The spirit of the strikers was aroused, and large crowds attended union rallies and joined the picket line. In early May the Manville-Jenckes Company evicted over sixty families of strikers from company housing, and the union set up a tent colony, called New Town, for the homeless strikers. Several weeks later Ella May Wiggins discovered that the spring she used for drinking water had been poisoned. She went into Loray to report the incident and found that there had been prowlers around the tent colony. In response, the strikers increased their guard.

On the evening of 7 June 1929 deputies disrupted a union rally and broke up a picket line composed of women and children; later the same night a shooting incident in the tent colony injured one unionist and four policemen and fatally wounded the chief of the Gastonia police, D. A. Aderholt. Seventy-one union members and organizers were arrested and held incommunicado in the Gastonia city jail for one week. Most were released, but sixteen defendants were detained in the Gaston County jail for six additional weeks before being indicted for the shootings. Following two days in court in Gastonia, the defense obtained a change of venue to Charlotte, in neighboring Mecklenburg County. On 26 August the trial of the sixteen union members began. After days of testimony a mistrial was declared on 9 September, when one of the jurors reportedly was disturbed after viewing an effigy of Chief Aderholt brought into the courtroom by the prosecution. That evening in Gastonia, an angry mob of over one hundred men formed in response to the dismissal of the case, wrecked the union's headquarters in Gastonia and Bessemer City, and terrorized, kidnapped, flogged, and threatened to kill several union members. The next day, 10 September, the mob re-formed, raided the Charlotte headquarters of the International Labor Defense (ILD), the group handling the case for the NTWU defendants, and attempted to remove one NTWU organizer from jail in order to lynch him. To protest such lawlessness the NTWU announced that a huge rally of all union people in Gaston County would be held in South Gastonia on 14 September.

As the events of the Gastonia strike unfolded, Wiggins recorded them in song. The strike, the union, and the men and women in jail all became the subjects of her ballads. After the murder of the police chief, Wiggins sang to the strikers: "Come all of you good people, And listen to what I tell; The story of Chief Aderholt, The Man you all knew well." Drawing from traditional mountain ballads, Wiggins put new words to old tunes while carefully observing the conventions of the unfamiliar songs. Her lyrics, "Toiling on life's pilgrim pathway—Wheresoever you may be, It will help you fellow workers—If you will join the ILD," became a popular strike song. Wiggins, or Ella May, as she was always called, sang before large groups of workers in fervent tones, with great seriousness. As folklorist Margaret Larkin wrote in 1929, Wiggins's songs were "better than a hundred speeches." This quiet young woman's untaught alto voice rang out simple, monotonous tunes that captivated those who listened. Her six-versed ballad entitled "The Mill Mother's Lament" documented her personal struggle to support her children:

We leave our homes in the morning,

We kiss our children good bye,

While we slave for the bosses,

Our children scream and cry.

But understand, all workers,

Our union they do fear,

Let's stand together, workers,

And have a union here.

This ballad, as each of Wiggins's songs, expressed her faith in the union, the only organized force she had encountered that promised her a better life.

Ella May was to sing her ballads and speak to the strikers at the NTWU protest rally on 14 Sept. 1929. Early that morning the Manville-Jenckes forces mobilized hundreds of men, including many newly sworn-in deputies and vigilantes, to disperse those attending the rally; they set up roadblocks in all directions. A short time before the rally was to begin, a group of twenty-two unarmed union members, strikers, and sympathizers, Ella May Wiggins among them, traveled in a truck from Bessemer City to the rally site south of Gastonia. Wiggins had insisted that none of the strikers carry weapons. The truck was halted at one of the roadblocks where armed men ordered the workers to return to Bessemer City "on pain of death." The strikers turned their truck around and headed away from the meeting, as ordered, only to be pursued by several carloads of armed men. After a short distance, one of the cars passed the truck and stopped in its path. The truck driver, unable to brake quickly enough, ran into the car, and workers riding in the back of the truck tumbled out. For a moment, while the others scrambled back into the truck, Ella May Wiggins stood in the bright sunlight, leaning against the side rail. Then, the mob opened fire and she fell into the truck bed gasping, "Oh, my God, they've shot me." Wiggins died in the arms of Charley Shope, who had stood near her in the truck. The other strikers, two of whom were wounded, fled into a nearby field as the mob continued to fire their guns.

Immediately after Ella May Wiggins's death the Communist leadership of the NTWU announced that there would be a one-day strike to protest the murder; the ILD demanded the arrest of the men who had killed Wiggins. Union leaders were certain that Ella May had been deliberately shot for her interracial organizing and her role as balladeer and speaker. Claimed by the NTWU as a martyr for its cause, she was heralded in union and ILD campaigns nationwide. Among North Carolina liberals opposed to the Communist NTWU but appalled by the turn of events in Gastonia, Wiggins became a cause célèbre. Frank P. Graham, president of The University of North Carolina, wrote: "Her death is, in a sense, upon the heads of us all." He argued that he saw in Wiggins "not her mistaken Communism, but her genuine Americanism."

After her death, pressure from local strikers, North Carolina liberals, and national political organizations led Gaston County mill owners to reduce working hours to fifty-five per week, to improve conditions in the mills, and to extend welfare work in the textile villages. Although liberal groups throughout the state and national organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union and the ILD severely criticized Gaston County authorities, no bills of indictment were returned for the killing of Ella May Wiggins until six weeks after the murder when Governor O. Max Gardner, himself a mill owner, reopened the investigation. At that time, five employees of the Loray Mill were indicted. Despite the existence of over fifty eyewitnesses, however, these men were acquitted in a trial held in Charlotte in March 1930.

In the decades after 1929 Ella May became both a major figure in historical accounts of the Gastonia strike and a legendary character in southern fiction by authors including Mary Heaton Vorse, Loretto Carroll Bailey, Myra Page, and Grace Lumpkin. A mill hand known as the "songstress of the mill workers," she remains North Carolina's most famous folk heroine.

Ella May Wiggins was buried in an unmarked grave in Bessemer City's public cemetery. Wreaths from the NTWU, the ILD, and the Workers' Defense League adorned her plain pine coffin. The calm dignity of the funeral, attended by hundreds of mill workers, marked the end of the NTWU's organizing efforts in Gastonia. Wiggins, pregnant at the time of her death, was survived by her five children: Myrtle, 11; Clyde, 8; Millie, 6; Albert, 3; and Charlotte, 13 months. The children assumed their mother's maiden name to help hide their identity in the face of threats made to them amid the publicity surrounding their mother's murder. They were put in an orphanage. On 14 Sept. 1979, fifty years after the day of the 1929 shooting, North Carolina women from the Gastonia area held a memorial service in Bessemer City and placed a permanent marker on the grave of Ella May Wiggins.

References:

Loretto Carroll Bailey and James Osler Bailey, "Strike Song: A Play of Southern Mill People" (typescript, North Carolina Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill)

Fred E. Beal, Proletarian Journey: New England, Gastonia, and Moscow (1937)

Charlotte Observer , 15–18 Sept. 1929

Eugene Feldman, "Ella Mae [sic ] Wiggins: North Carolina Mother Who Gave Her Life to Build a Union," Southern Newsletter 2 (March–April 1957), and "Ella May Wiggins and the Gastonia Strike of 1929," Southern Newsletter 4 (August–September 1959)

Frank Porter Graham Papers (Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill)

Labor Defender 4 (October 1929); Margaret Larkin, "The Story of Ella May," New Masses 5 (November 1929), "Tragedy in North Carolina," North American Review 208 (1929), and "Ella May's Songs," Nation 129 (9 Oct. 1929)

Grace Lumpkin, To Make My Bread (1932)

Dan McCurry and Carolyn Ashbaugh, eds., "Gastonia, 1929: Strike at the Loray Mill," Southern Exposure 1 (Winter 1974)

F. Ray Marshall, Labor in the South (1967)

National Organization of Women, Let's Stand Together: The Story of Ella Mae [sic] Wiggins " (pamphlet, Metrolina chap., Charlotte), September 1979

Dorothy Myra Page, Gathering Storm (1932)

Liston Pope, Millhands and Preachers (1942)

Raleigh News and Observer , September 1929

George Brown Tindall, The Emergence of the New South, 1913–1945 (1967)

Tom Tippett, When Southern Labor Stirs (1931)

Mary Heaton Vorse, Strike ! (1930)

Mrs. Merritt Wandell, Waverly, N.Y., personal contact

Vera Buch Weisbord, A Radical Life (1977)

Workers and Allies: Female Participation in the American Trade Union Movement , Smithsonian Institution (1975)

Image Credits:

"Ella May Wiggins." Photo courtesy of the Gaston Gazette. Available from http://www.gastongazette.com/sections/article/gallery/?pic=1&id=60526&db=gaston (accessed April 30, 2012).

1 January 1996 | Frederickson, Mary E.