(Old) Tassel

fl. 1757 - d. June 1788

Old Tassel (Tossel, Tassell) was a Cherokee diplomat, political leader, and treaty negotiator. He served the Cherokee nations during the French and Indian War, Cherokee Wars, and the American Revolution. Tassel also negotiated extensively with the State of Franklin during its existence (1784-1788). He was known by many names, which included Koatohee, Corn Tassel of Toquo, Kahn-yah-tah-hee, Kaiyah-tahee, Onitositaii, or simply Tassel. Tassel was also a "First Beloved Man" of the Overhill branch of the Cherokee nation.

Old Tassel (Tossel, Tassell) was a Cherokee diplomat, political leader, and treaty negotiator. He served the Cherokee nations during the French and Indian War, Cherokee Wars, and the American Revolution. Tassel also negotiated extensively with the State of Franklin during its existence (1784-1788). He was known by many names, which included Koatohee, Corn Tassel of Toquo, Kahn-yah-tah-hee, Kaiyah-tahee, Onitositaii, or simply Tassel. Tassel was also a "First Beloved Man" of the Overhill branch of the Cherokee nation.

Tassel was likely born in the Overhill Cherokee village of Toqua. It is located in present-day Monroe County, Tennessee. In treaty negotiations in 1777 and 1785, Tassel documented his name “of Toquo(e).” Other European colonists of the period also referred to him as “Corn Tassel of Toquah.” Tassel’s parents are not known.

Tassel’s first documented appearances as a diplomat for the Overhill Cherokee people were during the French and Indian War. During the war, the British established Fort Loudon in 1757. It was the first English settlement west of the Smoky Mountains and is in present-day Monroe County, Tennessee. According to the papers of Governor William Lyttleton, Tassel served as an emissary to the commander of the fort for the Cherokee people.

Relations between the British and the Cherokee nations deteriorated during the war. In 1760, Cherokee warriors led by Oconostota besieged and captured Fort Loudon and the British evacuated. The British government petitioned American Indian nations from the area to send representatives to address the fall of the fort. Tassel served as a member of the “Upper Nations” Cherokee delegation. Subsequent British operations against Cherokee nations were hosted from Fort Prince George in South Carolina. Tassel was present at the fort in October 1760 and served as a peace ambassador for the Cherokee people. At Fort Prince George, he negotiated peace between the British and Cherokee nations with Oconostota, Attakullakulla, and Major M’Namar.

Tassel also served as a mediator for issues concerning the Proclamation of 1763. Many white colonists ignored the boundary and continued to settle west of the line. This angered many people of the American Indian nations west of the line like the Overhills Cherokee. Tassel continued to serve as a member of the British-Cherokee peace delegations after the war. In 1771, Tassel logged concerns about white transgressions of the Proclamation to Alexander Cameron. Cameron served as a representative of the British government among the Cherokee nation. The two dealt with each other frequently.

Tassel also served as a member of the Cherokee delegation during the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals and the Transylvania Purchase. Tassel, along with other Cherokee diplomats like Attakullakulla, Oconostata, and Savanooka (the Old Raven of Chota), negotiated the terms of the treaty with white colonists. Dragging Canoe, son of Attakullakulla, totally opposed the terms of the treaty and urged other leaders to do the same. He withdrew from the negotiations, and relocated south with many other prominent Cherokee leaders to form an alliance against white colonization known as the Chickamauga nation. Tassel and the others sympathized with Dragging Canoe and expressed concerns about white colonization of such a large area. According to a 1785 speech from Tassel, the terms of the treaty were never mutually agreed upon and Henderson had illegally taken the Cherokee hunting lands.

Tassel also served as a member of the Cherokee delegation during the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals and the Transylvania Purchase. Tassel, along with other Cherokee diplomats like Attakullakulla, Oconostata, and Savanooka (the Old Raven of Chota), negotiated the terms of the treaty with white colonists. Dragging Canoe, son of Attakullakulla, totally opposed the terms of the treaty and urged other leaders to do the same. He withdrew from the negotiations, and relocated south with many other prominent Cherokee leaders to form an alliance against white colonization known as the Chickamauga nation. Tassel and the others sympathized with Dragging Canoe and expressed concerns about white colonization of such a large area. According to a 1785 speech from Tassel, the terms of the treaty were never mutually agreed upon and Henderson had illegally taken the Cherokee hunting lands.

“The people of North Carolina have taken our lands without consideration, and are now making their fortunes out of them. I know Richard Henderson says he purchased the lands at Kentucky, and as far as Cumberland, but he is a liar, and if he was here, I would tell him so. If Attakullakulla signed this deed, we were not informed, but we know that Oconostota did not, yet we hear his name is to it. Henderson put it there, and he is a rogue.”

The treaty remained enacted for three years until it was amended. During the three-year period of white settlement, Oconostata, Attakullakulla, and Tassel experienced backlash from other members of the Cherokee nation.

By late spring 1777, Attakullakulla and Oconostata were both very old. They delegated some diplomatic representation of the Cherokee nation to Tassel and Savanooka. Cherokee diplomats, including Tassel, petitioned Patriot leaders for peace by the summer of 1777 due to the events of the Cherokee War of 1776 and Rutherford’s Campaign. The petitions resulted in peace treaties, and the most significant was the Treaty of Long Island on the Holston River in July 1777. The treaty location, the Long Island of the Holston River (at Kingsport in present-day East Tennessee) was an important religious and cultural place to the Overhills Cherokee people. At the treaty talks, Tassel condemned white violence during Rutherford’s Campaign, white colonization, and adoption of white culture among Cherokee people. He stated:

“You marched into our towns with superior force… spread fire and desolation wherever you pleased… Will you claim our lands by right of conquest? No! If you do, I will tell you that WE last marched over them… You say ‘Why do not the Indians till the ground and live as we do?’ May we not ask with equal propriety, ‘Why do not white people hunt and live as we do?’”

Tassel also sought peace and condemned destruction of the environment by white settlers. He claimed that social conditions were not fair and urged for fairness within the terms of the treaty. He stated:

“We wish, however, to be at peace with you. We do not quarrel with you for killing an occasional buffalo or deer on our lands, but your people go much farther… They kill all our game; but it is very criminal in our young men if they chance to kill a cow or hog in your lands.

"The Great Spirit has placed us in different situations… We are not your slaves… Your animals are tame while ours are wild… They are, nevertheless, as much our property as other animals are yours, and ought not to be taken from us without our consent, or for at least something of equal value.”

White treaty negotiators lessened the demands of the treaty after receiving Tassel’s speeches. Despite this, extensive land tracts were ceded to white settlers.

White treaty negotiators lessened the demands of the treaty after receiving Tassel’s speeches. Despite this, extensive land tracts were ceded to white settlers.

The Treaty of Long Island of the Holston River created a temporary peace between most Cherokee people and white settlers. However, Dragging Canoe and other Chickamauga sympathizers still fought against white settlement and the Patriot government. This was especially true as the British strategy in the American Revolution shifted south after 1780. At this point, the British government again called on the Cherokee people as allies. In July 1781, Tassel’s role as a diplomat for the Cherokee people changed. Oconostata had retired as a diplomat and named his son, Tuckasee, as his successor. Tuckasee had never served in an official capacity as a diplomat, and most Overhills Cherokee people did not support the choice. They already recognized Tassel politically and supported his nomination instead. As a result, Tassel became a formally recognized leader, or a "First Beloved Man," in Cherokee diplomacy. The title of “First Beloved” symbolized a person’s significant cultural status among certain groups of the Cherokee people. They believed that a deity known as “the Great Spirit,” spoke through the “Beloved” person. Beloved people were well-known people with a history of service to their community. Around this time, Tassel’s sympathies with Dragging Canoe had lessened. He began to align with the diplomacy of older chiefs as a pacifist. Despite complaints of white settlers “wanting land” and “plundering our hunters,” Tassel sought peace with them during this period.

Land disputes between white settlers and native Cherokee people were chronic in spite of the treaties. On September 25, 1782, Tassel issued complaints to Colonel Joseph Martin about “whites encroaching on Indian lands [and] shooting Indians.” The Long Island of the Holston River, despite being protected from official white settlements, was also targeted for settlement. Tassel further lodged complaints with Martin of “ammunition not being delivered” and that “Cherokee people [were] poor.” These complaints continued into early 1783. The same year, North Carolina’s General Assembly opened all Cherokee hunting grounds north and west of the French Broad and Tennessee Rivers to white settlement. In response, Tassel issued further complaints and petitions in 1784 with renewed fears of white aggression.

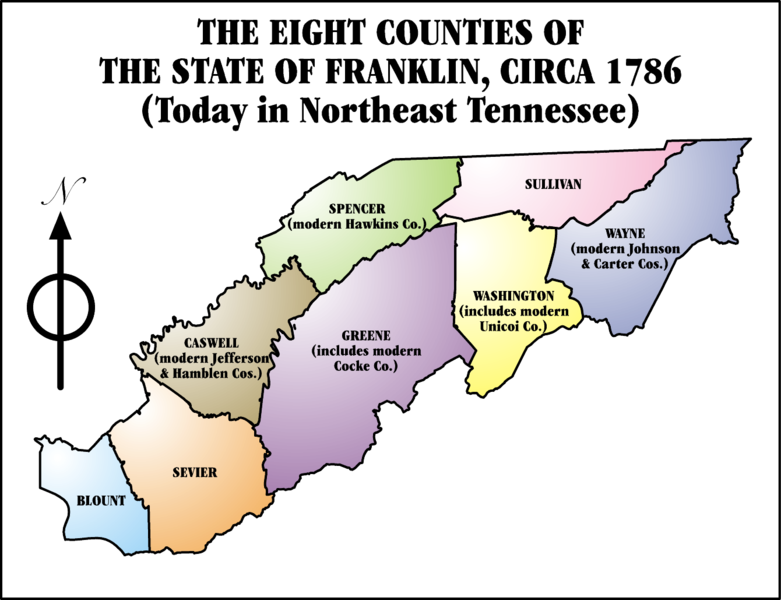

White colonization of Cherokee land also increased after the State of Franklin formed. On August 23, 1784, eight counties in western North Carolina (now Tennessee) seceded their lands from the state and would remain seceded until 1788. Franklin’s Declaration of Independence and the December 1784 Constitution both enshrined protection for white settlers against American Indian “raviges [sic].” As such, Franklin pursued a policy of colonization against American Indian nations like the Cherokee during its lifetime. Due to Franklin’s policies, Tassel dealt extensively with representatives of the state from 1784 until his murder in 1788.

On June 10, 1785, representatives of the State of Franklin signed the Treaty of Dumplin Creek with representatives of the Overhills Cherokee Nation. The treaty opened tracts of Cherokee land between the Holston and Little Rivers in Middle Tennessee to white settlement. The treaty offered no immediate compensation for settlement of the land. It “agree[d] that there shall be a liberal compensation made to the Cherokees for the land they have herein ceded and granted to the white people… in good faith.” The terms of the treaty were very favorable to white settlers. Tassel, Hanging Maw, and Dragging Canoe were not invited as part of the Cherokee delegation. The omission of senior Cherokee leadership allowed white Franklinites greater ease in claiming Cherokee lands at the talks. Tassel himself claimed that senior leaders of the Cherokee nations like himself were purposefully omitted from the discussion and misled by white negotiators about the actual terms of the treaty.

On June 10, 1785, representatives of the State of Franklin signed the Treaty of Dumplin Creek with representatives of the Overhills Cherokee Nation. The treaty opened tracts of Cherokee land between the Holston and Little Rivers in Middle Tennessee to white settlement. The treaty offered no immediate compensation for settlement of the land. It “agree[d] that there shall be a liberal compensation made to the Cherokees for the land they have herein ceded and granted to the white people… in good faith.” The terms of the treaty were very favorable to white settlers. Tassel, Hanging Maw, and Dragging Canoe were not invited as part of the Cherokee delegation. The omission of senior Cherokee leadership allowed white Franklinites greater ease in claiming Cherokee lands at the talks. Tassel himself claimed that senior leaders of the Cherokee nations like himself were purposefully omitted from the discussion and misled by white negotiators about the actual terms of the treaty.

“[Franklin authorities] sought liberty for [white settlers] that were living on the land to remain there, till the head men of their nation were consulted on it, which our young men agreed to. Since then we are told that they claim all lands on the waters of Little River, and call it their ground.”

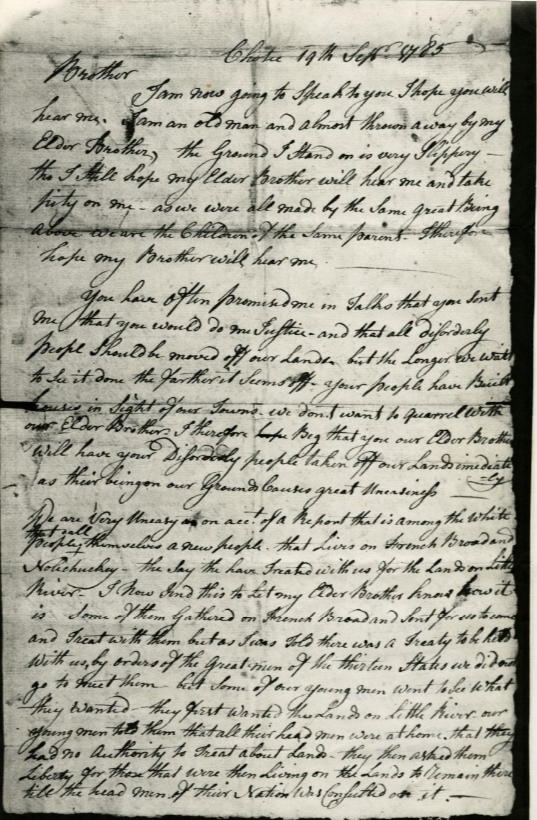

The State of North Carolina refused to recognize the treaty as Franklin had seceded from the state. The treaty talks also only included the Overhills Cherokee branch of the tribe and not others, despite the territorial cessions also affecting them. Tassel did not recognize the terms of the Treaty of Dumplin Creek until the Conference at Chota Ford and the Treaty of Coytoy in August 1786. Despite lack of recognition, white settlers under the State of Franklin continued to colonize the area. In September 1785, both Joseph Martin and Tassel contacted Patrick Henry, then governor of Virginia. Both sets of correspondence described “encroachment” of white Franklinites onto Cherokee lands despite the terms of previous treaties. Tassel’s letter specifically called on Henry to help protect Cherokee land against the State of Franklin.

Political negotiations regarding Cherokee lands continued into late 1785. From November 22 until November 28, 1785, treaty commissioners from the United States federal government met with Cherokee “Head-men and warriors.” The Cherokee delegation included Tassel (documented as “Koatohee, or Corn Tassel of Toquo”). The groups met at Andrew Pickens’ Hopewell Plantation in South Carolina. The 1785 Treaty of Hopewell was the first treaty that the United States government formally signed with the Cherokee nation. It established agreed-upon land boundaries for the United States and Cherokee nations.

In 1786, white commissioners forced Tassel and Hanging Maw to agree to the terms of the Treaty of Coytoy (Coyatee). Violent land disputes were widespread in lower and middle Tennessee. White settlers built homesteads on Native land outside of treaty boundaries and displaced people that already lived there. In some cases, they attacked and killed American Indian people they found in their settlements. Between April and June 1786, groups like the Chickamaugas responded with force and attacked white settlers and traders. Joseph Martin, in a letter to Governor Richard Caswell of North Carolina, documented the attacks:

“The 17th of [April 1786], the parties of Indians returned with fifteen scalps, sent several letters to Gen. [John] Sevier, which he read, as they were open; the informed the general that they had now taken satisfaction for their friends that were murdered, that they did not wish for war, but if the white people wanted war, it is what they would get.”

Other violent disputes involving the Creek (Muscogee) nation and the murders of white settlers angered colonists. In response, a white militia of 250 men marched into the village of Coytoy and killed two American Indian men. The murders violated the 1785 peace treaties established at Dumplin Creek and Hopewell. To address the violence, Sevier sent commissioners to negotiate a new treaty with the Cherokee people. At the talks, Tassel and Hanging Maw represented Cherokee interests. The treaty negotiations lasted from July 31st until August 3rd, 1786. They started at Chota Ford but ended at Coytoy. At the treaty talks, Sevier’s commissioners charged the Cherokee nation with the violence of the Creek people. In response, Tassel argued that “they are not my people that spilt the blood and spoiled the [treaty].” The new terms were sympathetic to white settlers. Cherokee people were not to attack any more white settlers or settlements. However, the treaty offered amnesty to violent white settlers as the Cherokee people “must blame your bad men for [our violence], for we do not know your bad men when they are in the woods.” The treaty also expanded white settlements from the “north side of the Tennessee [River] to the Cumberland Mountains.” The commissioners also threatened to “destroy any [Cherokee] town” that violated the new treaty. Under the threat of violence and with no compensation, Hanging Maw and Tassel agreed to the new treaty and signed the terms on August 3rd.

Other violent disputes involving the Creek (Muscogee) nation and the murders of white settlers angered colonists. In response, a white militia of 250 men marched into the village of Coytoy and killed two American Indian men. The murders violated the 1785 peace treaties established at Dumplin Creek and Hopewell. To address the violence, Sevier sent commissioners to negotiate a new treaty with the Cherokee people. At the talks, Tassel and Hanging Maw represented Cherokee interests. The treaty negotiations lasted from July 31st until August 3rd, 1786. They started at Chota Ford but ended at Coytoy. At the treaty talks, Sevier’s commissioners charged the Cherokee nation with the violence of the Creek people. In response, Tassel argued that “they are not my people that spilt the blood and spoiled the [treaty].” The new terms were sympathetic to white settlers. Cherokee people were not to attack any more white settlers or settlements. However, the treaty offered amnesty to violent white settlers as the Cherokee people “must blame your bad men for [our violence], for we do not know your bad men when they are in the woods.” The treaty also expanded white settlements from the “north side of the Tennessee [River] to the Cumberland Mountains.” The commissioners also threatened to “destroy any [Cherokee] town” that violated the new treaty. Under the threat of violence and with no compensation, Hanging Maw and Tassel agreed to the new treaty and signed the terms on August 3rd.

The Treaty of Coytoy pushed white settlement of Cherokee lands further. Culturally significant towns and places like Chota and the Long Island of the Holston River were threatened. During this period, Tassel routinely petitioned the governors of Virginia and North Carolina. “Brothers: I am going to speak to you, and I hope you will hear me and take pity on me, we were both made by the same Great Being above.” He asked them to intervene and protect Cherokee people from white settlement. Creek and Chickamauga raids also increased due to further white settlement. They continued through 1787 and 1788. White leaders urged Tassel to answer for each attack. Some, like Edmund Randolph (then governor of Virginia), even threatened Tassel, Cherokee people, and their towns with violence. On June 12, 1787, Tassel delivered a speech that was recorded and sent to Randolph. Tassel, representing the Cherokee people, demanded fair treatment. He claimed that he had consistently urged Cherokee people to respect signed treaties but that white settlers never similarly abided. He urged the governor to recognize their treatment and respond fairly:

“Your people has settled to our Towns; tho’ you say nothing about That… but if any Person tells you any thing that is bad about us you can believe that and threaten us with fire and sword. It is well known that I have done everything in my power to keep peace In my land and hold fast all the treaties and Good Talks and Keep my young men from doing mischief… I observe in every Treaty that we have had that a bound is fixt [sic], but we always find that your people settle much faster shortly after a Treaty than before. It is well known that you have Taken almost all our Country from us without our consent… but we have seen enough to know we are Used Ill… Had I suffered [my Young Men] to kill people…settling our land, I suppose they would not [have] settl’d so much of our country, but I would not suffer them to hurt and white man. I am Desirous of living in peace…”

Tassel continued to work for peace between Cherokee people and white settlers. On June 5, 1788, he recognized that the Creek people were responsible for the murders of about forty white settlers. In compliance with the Treaty of Coytoy, he pleaded for the Cherokee town of Hiawassee to be spared from retaliation. Again, Tassel denounced the violence and called for peace.

Despite his goals of peace, Tassel was murdered by the Franklin State Militia. In May 1788, a Cherokee liberation party from the Overhill villages of Chilhowe and Citico killed eleven members of a white colonist family, the Kirks, near the village of Chota. The attack party was led by Slim Tom and served to protest the terms of the Treaty of Coytoy. The Kirk family murders outraged white colonists in the Franklin territory. John Sevier assembled the Franklin state militia, including the one surviving member of the Kirk family, John. They marched towards the Overhill Cherokee villages to retaliate, despite little evidence of coordinated involvement. Several Overhill villages including Chilowe were attacked and destroyed in response. Tassel was present in Chilowe with the town’s chief, Old Abraham, during the time of the attacks in late June 1788. The Franklin State militia and its officers “ferried” the two chiefs to a “white flag of truce” meeting. The meeting, held at John Sevier’s tent in the Franklinite encampment, served to discuss the attacks and incident. At Sevier’s tent,

“John [and others] fell on the Indians, killed the Tassell, Hanging Man, Old Abram [Abraham], his son, Tassell’s brother and Hanging-Man’s brother, and took Abram’s wife and daughter–brought in 14 scalps–altogether a scene of cruelty.”

Despite no evidence of his involvement, Tassel was murdered in June 1788 by John Kirk and other members of the Franklin state militia.

Hanging Maw succeeded Tassel as a political “head-man” for the Cherokee people. The murder of Tassel (and others) ended peaceful negotiations and reinstated armed conflicts between white settlers and Cherokee people. The Chickamauga tribe, and others, publicized Tassel’s murder and united to avenge him. They pledged to resist further violence and white colonization. They were led by Dragging Canoe and John “Young Tassel” Watts. Violent land disputes in the Appalachian mountains persisted for three years after Tassel’s murder.

Many members, some prominent, of the Cherokee nations claimed relation to Tassel. Some members of Tassel’s family may or may not be related by blood. Tassel’s family included clan members who were considered and documented as brothers and sisters by Overhill Cherokee cultural practices. Tassel siblings included: “Doublehead and Pumpkin Boy,” the mother of chief John “Young Tassel” Watts, “Eughiootie” (Elizabeth Coody), “Sequeechee,” and Na-ni (Nancy, “Doublehead’s sister”). Tassel was also the brother or uncle of Wurteh Watts, mother of Sequoyah.

References:

Baker, Jordan. “The Cherokee-American War From The Cherokee Perspective.” Journal of the American Revolution. July 29, 2021. Accessed June 12, 2023 at https://allthingsliberty.com/2021/07/the-cherokee-american-war-from-the-....

Barksdale, Kevin T. The Lost State of Franklin: America's First Secession. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2010.

Brown, John P. Old Frontiers: the story of the Cherokee Indians from earliest times to the date of their removal to the West, 1838. New York: Arno Press, 1971.

Burns, Inez E., Daughters of the American Revolution Mary Blount Chapter (Blount County Tenn.), and Tennessee State Historical Commission. History of Blount County Tennessee; from War Trail to Landing Strip 1795-1955. Nashville: Printed by Benson Print, 1957.

Carter, Samuel, III. Cherokee Sunset: A Nation Betrayed: A Narrative of Travail and Triumph Persecution and Exile. First ed. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1976.

Dean, Nadia. “A Demand of Blood: The Cherokee War of 1776.” Published in the Magazine of Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian, vol. 14, no. 4 (Winter 2013). https://www.americanindianmagazine.org/story/demand-blood-cherokee-war-1776 (accessed December 12, 2023).

Evans, E. Raymond. “Notable Persons in Cherokee History: Ostenaco” in Journal of Cherokee Studies, vol. 1, no. 1. Cherokee, North Carolina: Museum of the Cherokee Indian. Summer 1976.

Goodpasture, Albert V. “INDIAN WARS AND WARRIORS OF THE OLD SOUTHWEST, 1730-1807.” Tennessee Historical Magazine 4, no. 2 (1918): 106–45. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42637395 (accessed November 2, 2023).

Haywood John. W.H. Haywood, pub. The Civil and Political History of the State of Tennessee from Its Earliest Settlement Up to the Year 1796. Knoxville, Tennessee: Tenase Company, 1969.

Hoxie, Frederick E, ed. The Oxford Handbook of American Indian History. First ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Hummell, Melissa Marie. “Corn Tassel Utsi'dsata, Beloved Man of the Overhill Cherokees.” Geni.com. August 25, 2023. https://www.geni.com/people/Corn-Tassel-Beloved-Man-of-the-Overhill-Cher... (accessed November 2, 2023).

Keedy, Edwin R. “The Constitutions of the State of Franklin, the Indian Stream Republic and the State of Deseret.” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 101, no. 4 (1953): 516–28. https://doi.org/10.2307/3309935 (accessed November 2, 2023).

Kelly, James C. “Oconastota,” in Journal of Cherokee Studies, vol. 3, no. 4. Cherokee, North Carolina: Museum of the Cherokee Indian, Fall 1978.

King, Duane and E. Raymond Evans. “Original Specimens of Eloquence: Speeches Given at the Treaty of Hopewill, 1785,” in Journal of Cherokee Studies, vol. 4, no. 2. Cherokee, North Carolina: Museum of the Cherokee Indian. Spring 1979.

Kutsche, Paul. A Guide to Cherokee Documents in the Northeastern United States. Metuchen, New Jersey: Scarecrow Press, 1986.

“Letter from Chief Old Tassel of the Overhill Cherokee to his Elder Brother, the Governors of Virginia and North Carolina.” Tennessee Virtual Archive. September 19, 1785. https://teva.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15138coll18/id/620/ (accessed November 2, 2023).

Mooney, James. Historical Sketch of the Cherokee. Chicago: Aldine Publishers, 1975.

Moore, John Trotwood, Austin Powers Foster, and S.J. Clarke Publishing Company. Tennessee the Volunteer State 1769-1923, vol. 1. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1923.

Palmer, William Pitt. Calendar of Virginia State Papers and Other Manuscripts From January 1, 1782, to December 31, 1784, Preserved in the Capitol at Richmond, vol. 3. New York: Kraus Reprint Corporation, 1968.

Palmer, William Pitt. Calendar of Virginia State Papers and Other Manuscripts From January 1, 1785, to July 2, 1789, Preserved in the Capitol at Richmond, vol. 4. New York: Kraus Reprint Corporation, 1968.

Pate, James P. “Treaty of Hopewell.” Mississippi Encyclopedia. April 14, 2018. http://mississippiencyclopedia.org/entries/treaty-of-hopewell/ (accessed November 2, 2023).

Phoenix Archives. “1785 Treaty of Hopewell.” Cherokee Phoenix. May 22, 2008. https://www.cherokeephoenix.org/news/1785-treaty-of-hopewell/article_321... (accessed November 2, 2023).

Ramsey, J. G. M. The Annals of Tennessee to the End of the Eighteenth Century : Comprising Its Settlement As the Watauga Association from 1769 to 1777 ; a Part of North-Carolina from 1777 to 1784 ; the State of Franklin from 1788 to 1790 ; the Territory of the U.s. South of the Ohio from 1790 to 1796 ; the State of Tennessee from 1796 to 1800. Kingsport, Tennessee: Kingsport Press, 1926.

“Ratified Indian Treaty 11: Cherokee - Hopewell, November 28, 1785.” National Archives Catalog. United States National Archives and Records Administration. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/82573544 (accessed November 2, 2023).

Rozema Vicki. Footsteps of the Cherokees: A Guide to the Eastern Homelands of the Cherokee Nation. Second ed. Winston-Salem, North Carolina: John F. Blair, 2007. https://www.overdrive.com/search?q=F36B79E1-9B7E-46CB-B8BA-BD51B6524464 (accessed November 2, 2023).

Saunders, William L., Walter Clark, Stephen B Weeks, and North Carolina Trustees of the Public Libraries. The Colonial Records of North Carolina : Published Under the Supervision of the Trustees of the Public Libraries by Order of the General Assembly, vols 16-18, 20, 22. Wilmington, North Carolina: Broadfoot Publishing, 1993.

Smith, D. Ray. “Dragging Canoe, Cherokee War Chief.” . January 2006. http://discoverkingsport.com/h-chief-dragging-canoe.shtml (accessed November 30, 2023).

“Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings.” Explorers and Settlers. National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/explorers/sitee28.htm (accessed November 2, 2023).

Toomey, Michael. "Transylvania Purchase." Tennessee Encyclopedia. March 1, 2018. http://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/transylvania-purchase/ (accessed August 8, 2024).

Williams, Samuel Cole. History of the Lost State of Franklin. Rev. ed. New York: Press of the Pioneers, 1933.

Williams, Samuel Cole. “Tatham’s Characters Among the North American Indians.” Tennessee Historical Magazine 7, no. 3 (1921): 174–79. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44702575 (accessed November 30, 2023).

Williams, Samuel Cole and Tennessee State Historical Commission. Tennessee During the Revolutionary War. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1974.

Williams, Wiley J. "Transylvania Company." NCpedia.org. Originally published in The Encyclopedia of North Carolina, 2006. https://www.ncpedia.org/transylvania-company (accessed August 8, 2024).

Additional Resources:

Daniel, Michelle. “From Blood Feud to Jury System; The Metamorphosis of Cherokee Law from 1750 to 1840.” American Indian Quarterly 11, no. 2 (1987): 97–125. https://doi.org/10.2307/1183692 (accessed November 30, 2023).

“The Cherokees: They Were Here First.” AmRevNC.com. https://amrevnc.com/cherokees/ (accessed November 30, 2023).

Image Credits:

“Long Island, Kingsport, TN.” WorldIslandInfo.com. Photograph. February 20, 2009. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Long_Island,_Kingsport,_TN_(11523602094).jpg (accessed January 11, 2024).

“The Eight Counties of the State of Franklin, Crica 1786 (Today in Northeast Tennessee).” Wikimedia Commons. Iamvered. January 31, 2006. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:8FranklinCounties.png (accessed January 11, 2024).

The Treaty of Sycamore Shoals. Wikimedia Commons. Lunette within the Kentucky State Capitol, Frankfort, Kentucky. Thomas Gilbert White. 1908.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Treaty_of_Sycamore_Shoals_-_Kent... (accessed January 11, 2024).

Timberlake, Henry. “A draught of the Cherokee Country: on the west side of the Twenty Four Mountains, commonly called Over the Hills.” Map. Circa 1765. Nashville, T.N: Tennessee State Library & Archives. https://teva.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15138coll23/id/352 (accessed January 11, 2024).

27 February 2024 | Dease, Jared