African Americans

by Roberta Sue Alexander, Rodney D. Barfield, and Steven E. Nash, 2006.

Additional research provided by Joseph W.Wescott II and Wiley J. Williams.

Part i: Introduction; Part ii: Life under slavery and the achievements of free Black people; Part iii: Emancipation and the Freedmen's Fight for Civil Rights; Part iv: Segregation and the struggle for equality; Part v: Emerging roles and new challenges; Part vi: References

Part II: Life under slavery and the achievements of free Black people

The eight Lords Proprietors who received the Carolina charter from England’s King Charles II in 1663 planned from the beginning to employ the labor of enslaved people in their colony. The Fundamental Constitutions drafted in 1669 explicitly mention the enslavement of Africans. Barbadians, who were among the first colonists to invest in Carolina, persuaded the Proprietors to institute a headright system under which settlers received a certain amount of acreage for each ‘‘Negro-Man or Slave’’ and ‘‘Woman-Negro or Slave’’ brought to the province.

The eight Lords Proprietors who received the Carolina charter from England’s King Charles II in 1663 planned from the beginning to employ the labor of enslaved people in their colony. The Fundamental Constitutions drafted in 1669 explicitly mention the enslavement of Africans. Barbadians, who were among the first colonists to invest in Carolina, persuaded the Proprietors to institute a headright system under which settlers received a certain amount of acreage for each ‘‘Negro-Man or Slave’’ and ‘‘Woman-Negro or Slave’’ brought to the province.

Yet slavery grew slowly in North Carolina. The colony’s treacherous coastline and poor harbors forced planters to purchase enslaved people in Virginia or South Carolina and to transport them overland or along inland water routes. Relatively few enslaved people were imported directly by sea, and those who were usually came from other mainland colonies or the West Indies. A small number arrived straight from Africa. In 1712 the entire Black population of North Carolina was estimated to be only 800. But as the eighteenth century progressed, the number of enslaved Africans in the colony exploded—from an estimated 6,000 in 1730 to about 41,000 in 1767. After the American Revolution and by the time of the first decennial census in 1790, the 100,572 enslaved people in North Carolina comprised one-fourth of its total population. From 1820 to 1860 the Black population stabilized at between 32 and 33 percent of the aggregate population, reaching 331,059 in 1860.

Most people who were enslaved lacked adequate clothing, shelter, and nutrition and worked long hours. Enslavers issued clothes twice a year, in the spring and autumn. Rations consisted of meat, meal, molasses, and potatoes. To supplement their diet, enslaved people planted their own gardens, hunted, and fished. In the rice growing districts, a task system had become fairly standard by the 1840s, and most work could be completed by midafternoon. During the harvest season, however, men, women, and children labored from dawn to dusk seven days a week. Working in gangs, often under Black drivers, enslaved people cleared new ground, rolled logs into heaps, planted crops, hoed, harvested, threshed, and transported crops to market.

The North Carolina legislature enacted the basic slave codes defining the social, economic, and physical place of bondservants in 1715 and 1741. In the ensuing years modifications followed. Slave patrols were instituted in 1753. Jurisdiction over enslaved people changed from special slave courts before 1791, to county courts, and finally to superior courts in 1816. It was not murder to kill a person who was enslaved until 1817. By the 1850s the slave code prohibited enslaved people from engaging in a wide range of behaviors and activities, such as being disrespectful to whites, trespassing against whites, intermarrying or cohabiting with free Black people, running away, producing forged papers, hiring themselves out, hunting with a gun, and preaching at a prayer meeting where enslaved people of different masters were gathered. Slave codes also forbade whites to teach enslaved or free black people to read and write (teaching rudimentary math skills was allowed).

Periodically, rumors of slave revolts swept North Carolina. The most serious incidents occurred in 1775–76 at the outset of the American Revolution and in 1780–81 as British troops under Lord Charles Cornwallis advanced across the state; in 1802, during the religious ferment of the Second Great Awakening, when enslaved people in both Virginia and North Carolina tried to organize a conspiracy; and in 1830–31, when the dual impact of David Walker’s Appeal (1829) and the Nat Turner Rebellion in Virginia (1831) was felt. In each instance, white hysteria sometimes magnified the actual danger, and many innocent enslaved people were persecuted, transported, or murdered.

Yet Black peoples’ desire for freedom was powerful, and their efforts to achieve it were often relentless. Runaways were frequent, and maroons in the Great Dismal Swamp lived for years unmolested by whites. For most enslaved Black people, release from bondage was a distant dream. Strict manumission laws across the South permitted emancipation only for ‘‘meritorious services’’ as determined by the courts. Quakers circumvented the law by giving enslaved people the ‘‘full benefit of their labour’’ or assigning liberated Black people to agents who would arrange for their transport to Haiti, Liberia, or the free-soil North. A few enslaved people managed to buy their own freedom and that of their families. John Carruthers Stanly of New Bern was emancipated in 1795, bought the freedom of his wife and family, and eventually became the largest Black enslaver in the South, owning at one time 163 enslaved people. From 1790 to 1860, manumission of African Americans steadily increased but never kept pace with the rise in the numbers of enslaved people.

By the 1830s hundreds of free Black people—some whose freedom had been bought, others whose legal status was determined by the fact that their birth mother had been free—owned businesses and property in North Carolina; some prospered and became an integral part of the economic community. The cabinetmaking business of free Black Thomas Day, headquartered in Caswell County, became one of the most successful enterprises in antebellum North Carolina. The population of free Black people was largest in the east and the Piedmont, and many freedpeople resided in towns. Around the end of the eighteenth century a significant number of free Black people in Virginia migrated to counties such as Halifax, Bertie, and Northampton in northeastern North Carolina; they were later joined by freedpeople from elsewhere in the state. From this demographic group would emerge the Black activists of the Reconstruction era. When North Carolina opted to leave the Union at the start of the Civil War, the state was home to more than 30,000 free Black Americans. That number, one of the largest in the nation, North or South, represented about 10 percent of the state’s total African American population.

By the 1830s hundreds of free Black people—some whose freedom had been bought, others whose legal status was determined by the fact that their birth mother had been free—owned businesses and property in North Carolina; some prospered and became an integral part of the economic community. The cabinetmaking business of free Black Thomas Day, headquartered in Caswell County, became one of the most successful enterprises in antebellum North Carolina. The population of free Black people was largest in the east and the Piedmont, and many freedpeople resided in towns. Around the end of the eighteenth century a significant number of free Black people in Virginia migrated to counties such as Halifax, Bertie, and Northampton in northeastern North Carolina; they were later joined by freedpeople from elsewhere in the state. From this demographic group would emerge the Black activists of the Reconstruction era. When North Carolina opted to leave the Union at the start of the Civil War, the state was home to more than 30,000 free Black Americans. That number, one of the largest in the nation, North or South, represented about 10 percent of the state’s total African American population.

Religion was another aspect of colonial society that had attracted free Black people who aspired to leadership and influence, and by the late 1700s many whites had accepted their participation in church affairs as nonthreatening to the social order. Such tolerance was encouraged by the First Great Awakening that swept the colonies in the mid-eighteenth century. The crusading zeal of Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians for the lowly and disinherited made thousands of converts in the decades leading to the Revolutionary War.

John Chavis was North Carolina’s most prominent antebellum Black minister. Born free in Oxford, Chavis received training at Princeton University and Washington Academy (now Washington and Lee University) before he was recognized in 1801 by the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church. After serving as a missionary outside the state for several years, he was appointed minister to Presbyterian churches in Granville, Wake, and Orange Counties. As he traveled his circuit for more than 20 years, Chavis drew general praise for his ‘‘prudence and piety.’’ Perhaps his more lasting contribution was the organization of a school in Raleigh, where Chavis taught white children by day, including future political leaders, and free Black people in the evening. His school was considered one of the best in the state.

The activities of North Carolina’s free Black citizens were nevertheless limited by many laws and customs. At various times during the antebellum era, freedpeople were not allowed to carry guns, to testify against whites in court, or to compete in business on an equal basis with whites. Their movements and right to assemble were also restricted. Until 1835, freedmen could vote in North Carolina, but the new state constitution of that year disfranchised them while extending more direct representation to white males. This marked the beginning of additional restrictions for free Black people as well as people who were enslaved, culminating in the 1861 law prohibiting African Americans from owning or controlling enslaved people—and by extension making it impossible for freedpeople to redeem others from slavery. In the years prior to the Civil War, free Black people in North Carolina faced further hardships as their rights were systematically diminished.

Keep reading > Part III: Emancipation and the Freedmen's Fight for Civil Rights ![]()

Educator Resources:

Grade 8: An Overview of Slavery through Rotating Stations. http://civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2012/05/SlaveryRotatingStations.pdf

Grade 8: Slavery, Naval Stores and Rice Plantations in Colonial North Carolina. North Carolina Civic Education Consortium. civics.sites.unc.edu/files/2012/04/SlaveryNavalStoresRicePlantations.pdf

Image credits:

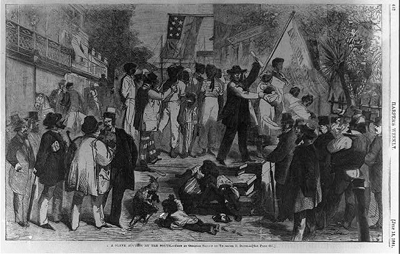

Davis, Theodore. 1861. "A slave auction at the south." Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. Reproduction no. LC-USZ62-2582. Online at http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/cph.3a06254. Accessed 11/2011.

1 January 2006 | Alexander, Roberta Sue; Barfield, Rodney D.; Nash, Steven E.